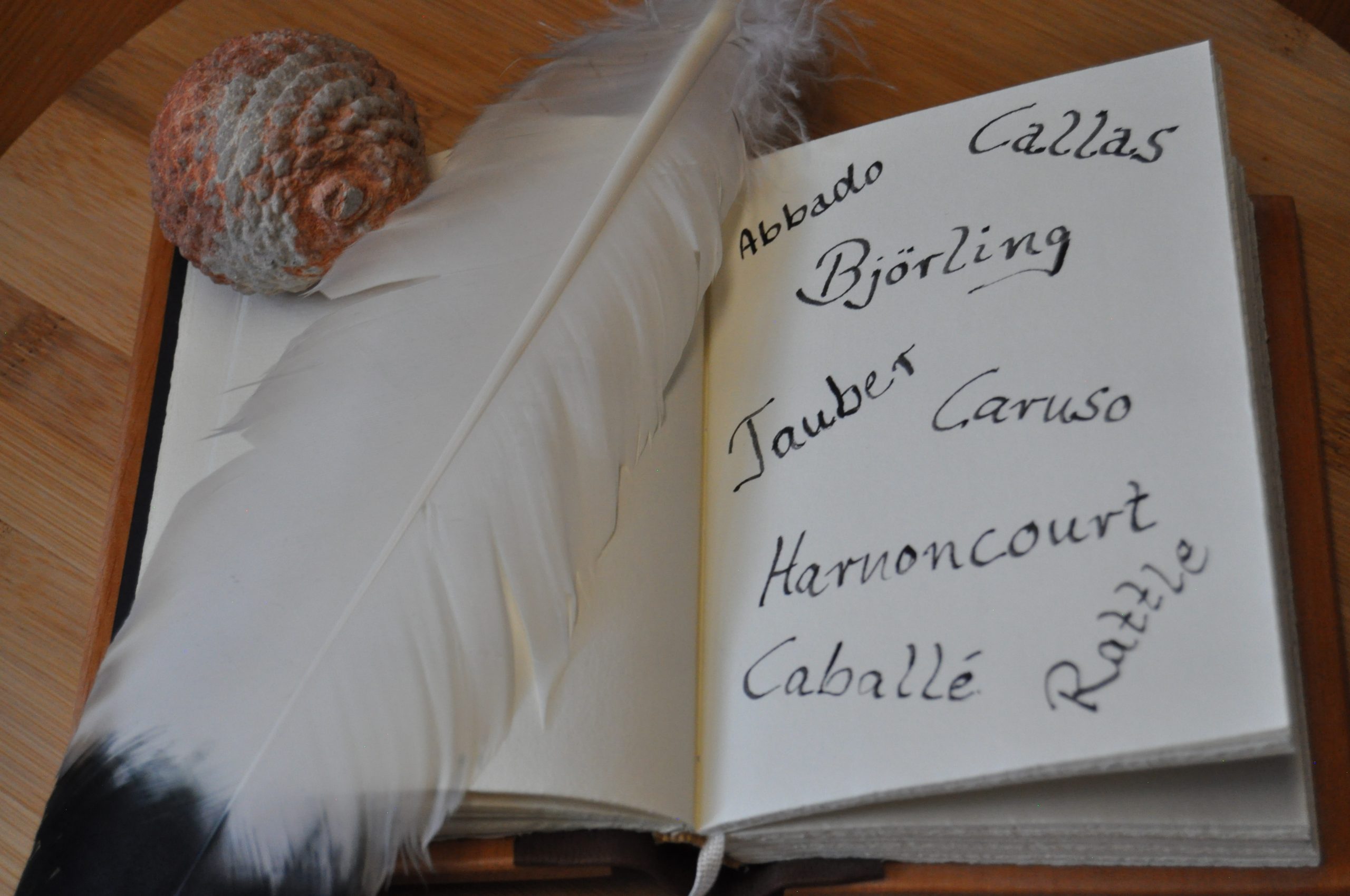

Although he undoubtedly belongs to the very great conductors, he never counted himself among the “greats”: for him, there was no such thing as a “great” conductor. For him, it was the composer and his music that stood in the center of attention and determined the musical work of a conductor to a large extent. For Abbado, the word “work” was to be avoided at all costs in connection with music: Music was not work for Abbado, but a “great, deep passion,” as he once emphasized in an interview.

Although the personalities of the two could not have been more different, Herbert von Karajan encouraged the young Claudio Abbado in his early career: Abbado came from a musically inclined Milanese family, but this by no means guaranteed that he would one day be a very successful conductor.

In the sixties, Abbado had already won some decisive prizes that were important for a career as a conductor: Among others, Abbado won the prestigious Mitropoulos Prize for Classical Music in 1963. But if Karajan had not invited him to conduct a performance of Mahler’s Second Symphony at the Salzburg Festival in 1965, Abbado’s career would hardly have been so successful.

Abbado didn’t want to be “moderately good” at many things; he wanted to be really good at one thing: That was conducting.

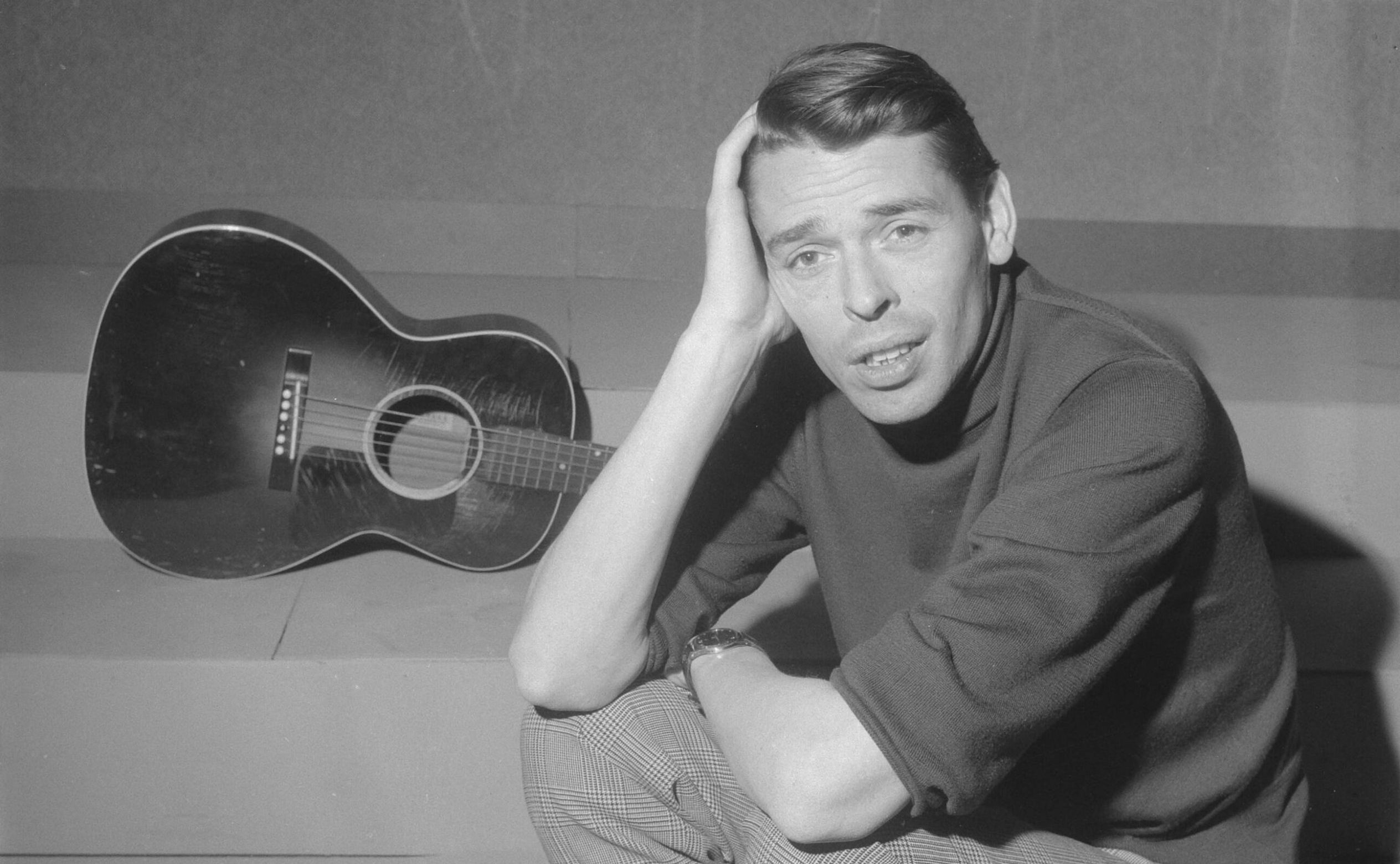

Conducting, composing or playing the piano?

Born into a musical family is not a free pass to make it in the world of classical music: Claudio Abbado studied composition, conducting and the piano at the Giuseppe Verdi Conservatory in Milan. Subsequently, in the mid-fifties, at the age of about twenty, Claudio Abbado went to Vienna to study conducting under the Austrian conductor Hans Swarowsky.

Before that, Abbado had made the decision to concentrate on conducting: As many of his colleagues later reiterated, Abbado had been a gifted piano player – but he gave up that passion to concentrate entirely on conducting, which claimed all of his musical potential. Abbado didn’t want to be “moderately good” at many things; he wanted to be really good at one thing: That was conducting.

After winning the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s Koussevitzky Prize in 1958, Abbado made his debut at Teatro alla Scala in Milan two years later.

Teatro alla Scala

The Teatro alla Scala was to play a special role in the life of Claudio Abbado: In the sixties, Abbado was very often at the conductor’s podium for opera world premieres and for new productions of well-known operas. After Abbado had more than convinced the Italian opera public, which is highly critical, of his unique art of conducting at numerous premieres, he was offered the post of chief conductor of the Teatro alla Scala at the age of only 35. From 1971 to 1986 Claudio Abbado was chief conductor of La Scala in Milan, leading one of the most prestigious orchestras in the world. The legacy of the Abbado era at La Scala in Milan cannot be captured only in musical key points: Abbado realized that the world of classical music had to be, and remain, accessible to a broad mass of people, so that it would be able to withstand the currents of the media world, which were changing every day. Many young people – including students who were definitely interested in classical music – and also workers were completely disconnected from classical music even then. This had not least to do with the fact that classical music is still often said to appeal primarily to an “elitist” audience. Claudio Abbado wanted to dispel this prejudice: he created a music program specifically for “students and workers” that was intended to enable those population groups to gain access to the world of classical music.

Young talent: “Still entirely free for music”

There is no question that Herbert von Karajan saw in Claudio Abbado not only a very gifted conductor, but one day a successor to his post as chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. This was despite the fact that Abbado was rather suspicious of the institutional music business throughout his life. Although Abbado held numerous chief conducting positions with the most renowned – institutionally organized – orchestras in the world, he was by no means afraid to launch his own orchestras – especially for young musical talent: Abbado founded, among others, the European Youth Orchestra, the European Chamber Orchestra, the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra and the Orchestra Filarmonica della Scala.

Young musicians are “still entirely free for music,” Abbado once pointed out in an interview: Although he founded so many orchestras, he always remained modest – the “overlaps” between the individual orchestras were very large, he once emphasized. Nevertheless, through his initiatives he gave many young, talented musicians a chance to showcase their talent on stage and express their passion for classical music.

For Claudio Abbado, making music was a communal experience.

One cannot make music alone

When Claudio Abbado took over as chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic in 1989, one thing was certain: it was the beginning of a new era. Before him, the post had been held for a proud 35 years by Herbert von Karajan, who had been dubbed the “General Music Director of Europe.” Only his death could topple Karajan from this throne.

Although Abbado’s tenure as chief conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic was considerably shorter than Karajan’s, at around 13 years, his tenure saw numerous significant changes in the Philharmonic’s structure: Abbado also awakened the awareness among the Berlin Philharmonic that the future of classical music would be in young hands. With his “Berliner Begegnungen” (Berlin Encounters) initiative, he created an opportunity for young musicians to play with already established members of the orchestra, thus sharpening their musical sense. These encounters offered enormous opportunities for musical development for both generations, young and old.

For Claudio Abbado, making music was a communal experience: one cannot make music alone, Abbado once stated. The orchestra members who played under the Italian conductor’s baton remembered Abbado as an extremely flexible conductor who was aware of his responsibilities: Playing under Abbado’s baton was not a unilateral experience. The orchestra and the piece of music being interpreted benefited from a reciprocity that prevailed between orchestra and conductor.

He let the music speak

The most important figure in Claudio Abbado’s childhood was his grandfather, who taught ancient history at the University of Palermo and “seemed to learn a new language every year,” as Abbado later recounted in an interview. Another inspiring figure of his childhood was his mother, who was a pianist and writer: Claudio Abbado came from a family that greatly appreciated art in all its variations. It is therefore not surprising that Abbado himself had a great penchant not only for music, but also for literature and painting.

On the special art of conducting, Claudio Abbado once said:

“I am often asked, why are there these gestures, what does the conductor actually do? And it is difficult to explain. I usually try to make the gestures for the music. It’s not something rehearsed or prepared. It comes with the sound, with the music. When you’ve conducted a piece many times, you need to conduct less and less. Then you can concentrate more on the big bow, the big line.”

It was rare to hear such words from Abbado: The exceptional conductor was a man of few words and let the music speak.

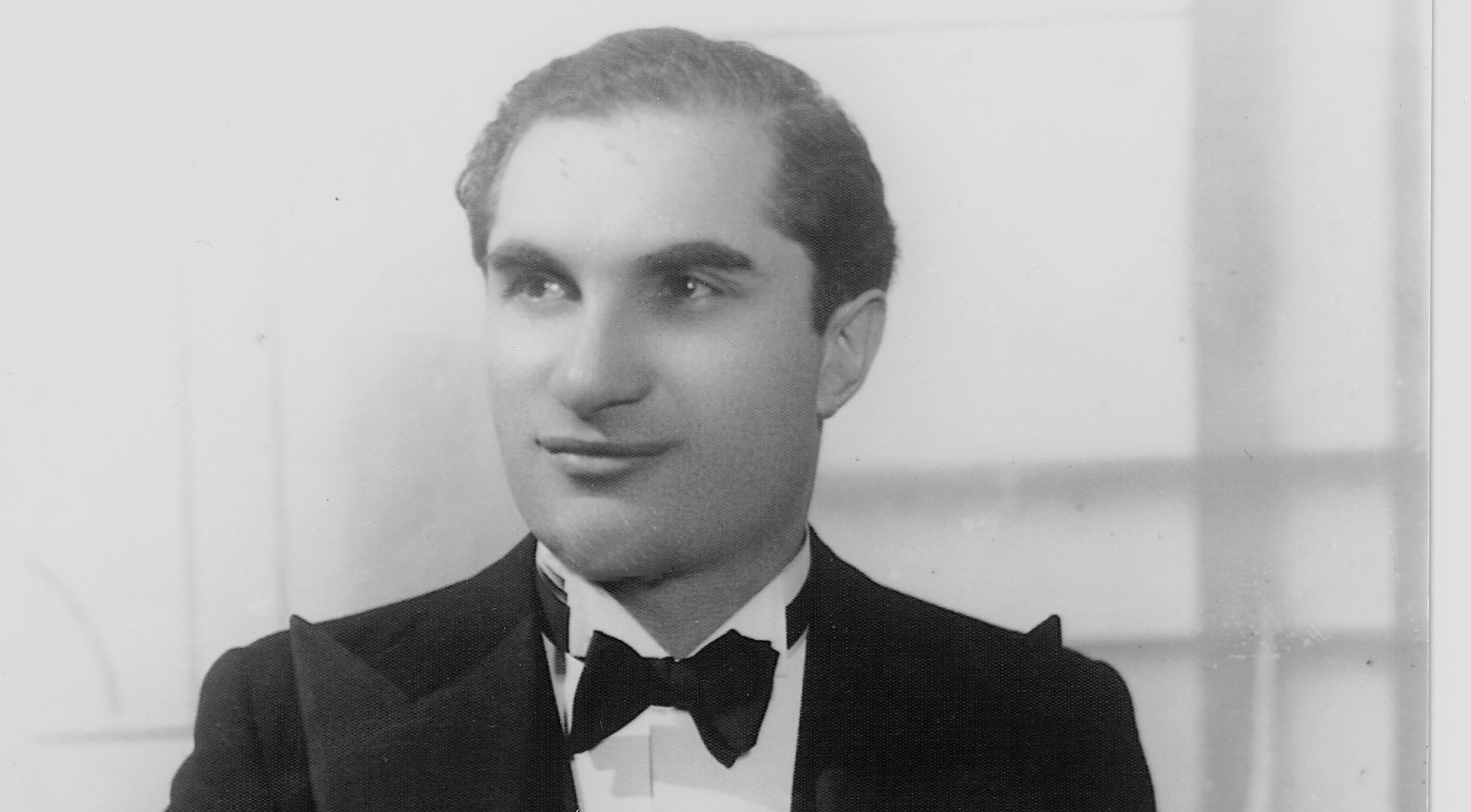

Cover picture: Claudio Abbado receives the AVRO Audience Award Classical 81 (1982)

Picture credit: Fotograaf Croes, Rob C. / Anefo, Nationaal Archief, CC0

Main sources: The documentary “Claudio Abbado – The Silence that follows the music”, 1996 (Directed by Paul Smaczny) and an interview from 2013 on the occasion of Claudio Abbado’s 80th birthday.

Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français