Continued from part one

At the end of 1935, a radio broadcast with Joseph Schmidt was broadcast to the United States: sitting in front of a radio receiver in New York, the music manager Sol Hurok signed Schmidt for a guest performance in the United States in the spring of 1937. In 1936, another opportunity arose for Schmidt to give concerts in Germany: However, the political situation had become increasingly tense, so the concerts were cancelled at the last minute.

But in Germany’s neighbouring countries, Joseph Schmidt was in demand as never before: on 5 July 1936, the tenor performed in front of 100,000 people in Birkhoven, Holland. By the standards of the time, this was a concert of superlatives – such crowds at concerts were rare. These crowds show just how much of an impact the tenor had in the thirties. Joseph Schmidt was now not just a tenor, he was a star tenor.

Vienna was his last anchor in a world he no longer recognised.

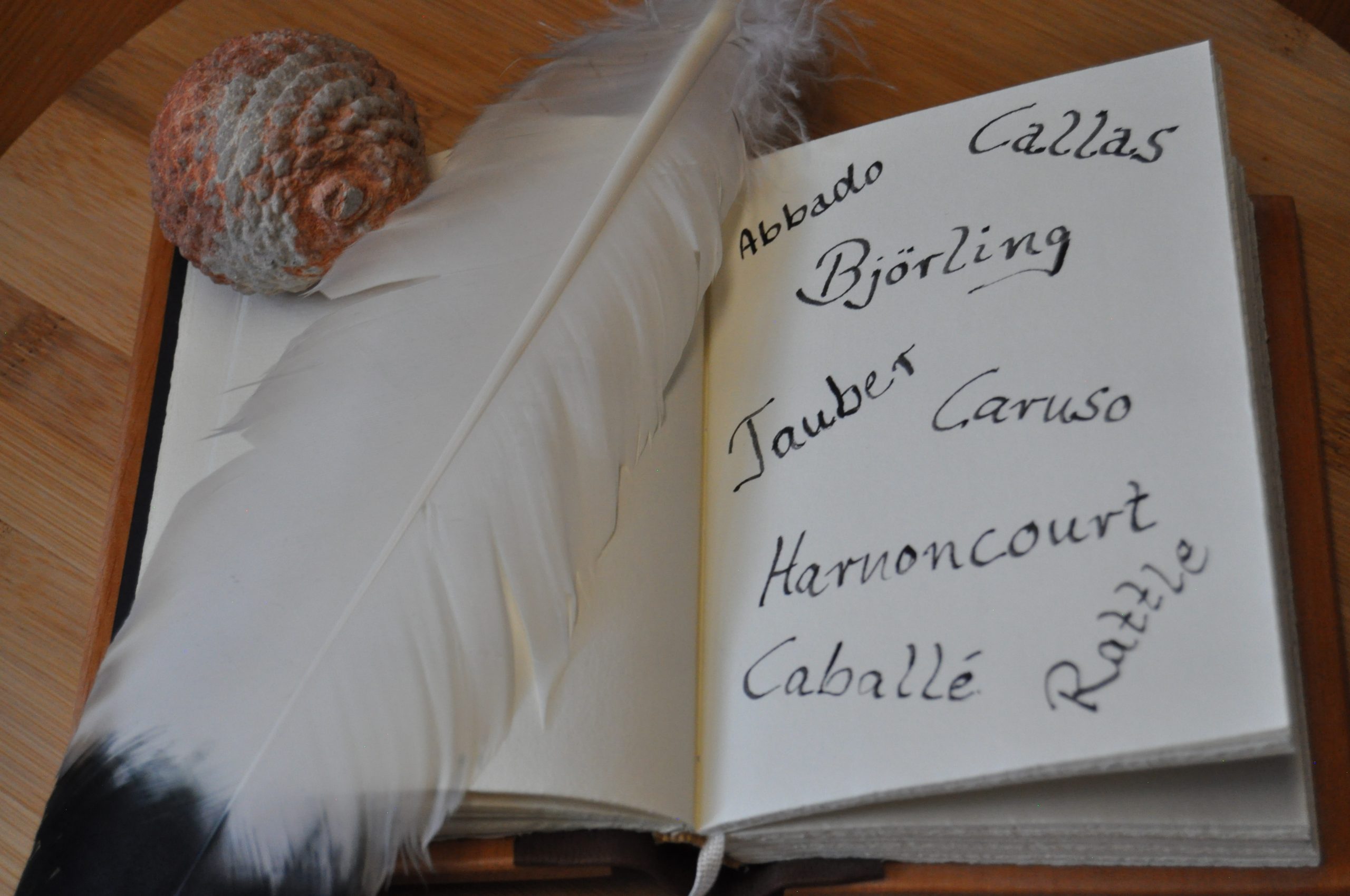

Joseph Schmidt sings…

In the meantime, European radio broadcasts all over the world had made the announcement “Joseph Schmidt sings…” a guarantee of artistic quality.

This had not least to do with the fact that Schmidt starred in English versions of his German-language films at the Elstree Studios of British International Pictures between 1936 and 1938. During these years Schmidt had numerous shooting sessions in London – but the tenor was by no means willing to leave Vienna in those days. Vienna was his last anchor in a world he no longer recognised: Schmidt continued to believe that sooner or later the situation would relax and he would be able to pursue his career.

Before Joseph Schmidt embarked on his journey to the United States for his guest performance in the spring of 1937, he gave his very last concert in Germany on 24 January 1937: his last concert tour through Germany, which took him to Frankfurt and Berlin, was particularly close to Schmidt’s heart. However, the concerts did not take place without further ado, they had to be approved beforehand in a lengthy process: It gradually dawned on Schmidt that he could no longer pursue his career in the German-speaking world…

The path to the concert hall

“The Tiny Man With The Great Voice” – these headlines greeted Schmidt in New York in the spring of 1937. For Schmidt, his guest appearance in the USA was a premiere in many respects: Not only had he never sung overseas before, he was given access to a new world.

In this new world he first had to learn to find his way around: His debut at New York’s Carnegie Hall was scheduled for 7 March 1937.

With this Carnegie Hall debut, Joseph Schmidt had proven that he could exploit the full potential of his voice even without a microphone. Things for European artists were anything but easy in the United States at the time – Schmidt was able to captivate American music lovers with his performances.

“It is Joseph Schmidt’s sincere wish to be accompanied only by a Steinway grand piano”: Advertisements like this soon appeared in the American newspapers, proving that the American press had become friends with the tenor. The radio tenor Joseph Schmidt had found his way into the concert hall. Would he also make the long hoped-for breakthrough on an opera stage? In Europe, things were not going well for him at the time: during his time in America, the performance of the film My Song Goes Round the World was banned in Germany on 1 October 1937.

At the end of the 1930s, there was no longer any place in Central Europe for an artist like him: Joseph Schmidt felt this.

Debut on the opera stage – despite adversity

After his trip to America, which ended in February 1938, Joseph Schmidt initially returned to Vienna: a contract with the music manager Sol Hurok was ready to be signed for the 1939/40 season – Schmidt initially postponed signing the contract. When Austria became part of the German Reich and the artists’ refuge Vienna was gone from one day to the next, the tenor decided to emigrate to Belgium: Despite these precarious circumstances, the contract with Sol Hurok remained unsigned and Joseph Schmidt never set foot on American soil again in his life. The exact motives that led Joseph Schmidt to this decision have not been clarified to this day.

What is certain is that Joseph Schmidt was able to fulfil his dream of standing on an opera stage in Belgium. Although Joseph Schmidt’s performances in Belgium were frequently met with harsh criticism – not least due to political circumstances – the tenor gave his premiere in his first real opera role. From January 1939, Joseph Schmidt impersonated the role of Rodolfo in Puccini’s La Bohème in Brussels. He performed this role more than twenty times within a year – in April 1939 he even gave a guest performance in this role in Helsinki. This guest performance in Helsinki was one of the last successful performances Schmidt was to celebrate. In the meantime, it was anything but easy for Schmidt to land a success: Many critics simply humiliated the tenor, others openly attacked him. At the end of the 1930s, there was no longer any place in Central Europe for an artist like him: Joseph Schmidt felt this.

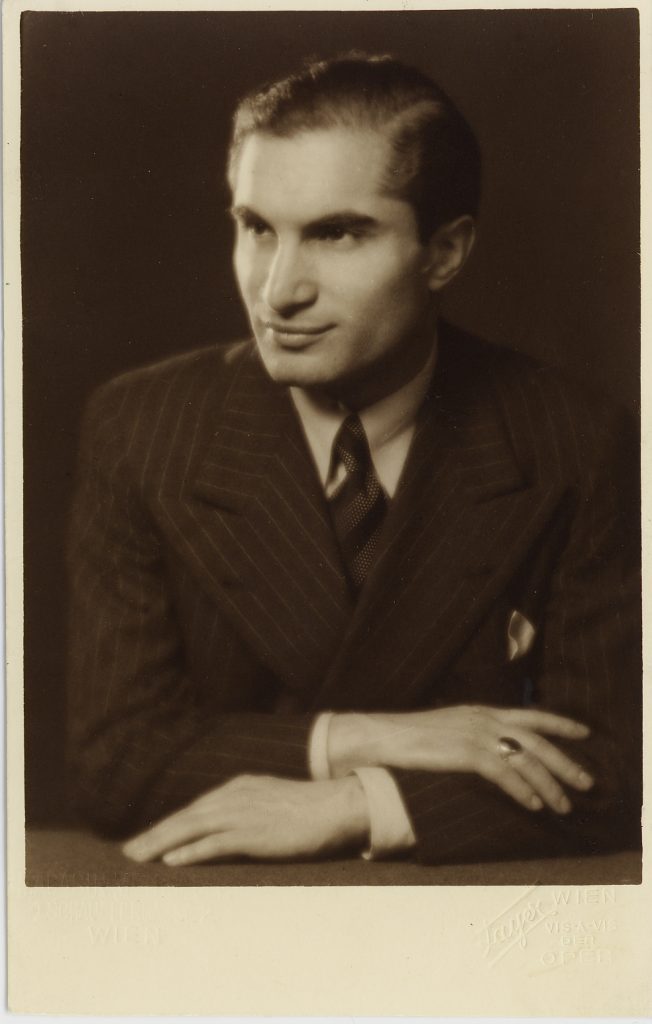

Picture by courtesy of the Joseph Schmidt Archive.

Running the gauntlet

On 10 May 1940, Joseph Schmidt wanted to present a new concert programme to his devotees in Brussels: But the course of history threw a spanner in the works. The Western campaign began on the same day and Joseph Schmidt was forced to flee Belgium: What followed was somewhat like running the gauntlet. Joseph Schmidt did not lack entry permits to other countries – at first he was simply not allowed to leave Belgium.

Art played only a subordinate role at this time. In the confusion that occurred during the last years of Joseph Schmidt’s life, there was no time or space left for what he actually wanted to do: To sing.

Schmidt’s escape route led him first to France and then to Switzerland, where his life came to an abrupt end on 16 November 1942 at the age of only 38.

A voice like his only existed once

The tenor has left an extensive legacy to posterity: Not only was he one of the first singers to achieve great fame through radio, he also recorded numerous vinyl records immortalising his unique voice.

It was his early death that contributed to Joseph Schmidt being remembered all the more by posterity: It is not only his path in life that matters, a path which could not be more exemplary for an artist of that time. The tenor broke conventions by achieving everything he set out to do in life despite numerous obstacles – of which his short stature was only one. He became a radio tenor, an actor and an opera tenor: the circumstances of his time did not prevent Joseph Schmidt from making the most of his unique musical talent. A voice like his only existed once.

Der Bussard expresses its gratitude to Mr Alfred Fassbind, head of the Joseph Schmidt Archive in Rüti near Zurich, for his cooperation.

The standard biographical work on Joseph Schmidt written by Mr Fassbind, published in a revised edition by Rüffer & Rub in 2021, was kindly provided to Der Bussard. The biography served as the main source for the article.

Publication information: Fassbind, Alfred A.: Joseph Schmidt – Sein Lied ging um die Welt [His Song Went Round the World], 2021 Rüffer & Rub

Cover picture: Joseph Schmidt 1937 in the studio of Lotte Jacobi in New York, by courtesy of the Joseph Schmidt Archive

Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français