Ella Fitzgerald once said she was the best singer who actually had no voice: Hildegard Knef is one of the most famous German actresses and singers of the 20th century. If one listens to a Hildegard Knef chanson, it is above all the arrangements that fascinate: Hildegard Knef was privileged to work with the best orchestra leaders of her time. For her vinyl records, she worked with Bert Kaempfert, Kurt Edelhagen and Gert Wilden. All these orchestra leaders have one thing in common: they shaped the typical sound of German chanson after the Second World War. Knef’s smoky voice did not thrive on its tonal range: Knef’s voice thrived on the lyrics she interpreted. Her deeply ironic lyrics, which often dealt with the illusions of human life, make Knef’s chansons a unique phenomenon.

Most of the talented male actors were drafted for military service and actresses were rare.

Illustrator

It all started with an apprenticeship as an illustrator at the UFA sound film studios in Berlin.

Regardless of her future: At an early age, Hildegard Knef was aware that she wanted to do something with the stage.

In her memoirs, Hildegard Knef describes how she was trained from 7:30 in the morning to 6:30 in the evening in all the things that the job of an illustrator for the UFA film studios required.

The fact that Hildegard Knef was one day invited by the film department to step in front of the camera was not least due to the outside circumstances at the end of the Second World War: What was left of the UFA film studios was held together by a few people. Most of the talented male actors were drafted for military service and actresses were rare.

Test recordings

Although Hildegard Knef was bored in the rooms of the UFA drawing – now windowless because of the bombings – she was exactly where she wanted to be: The world of theatre and cinema was closer to her than ever before.

At first, she had been invited by an employee of the UFA advertising department to do screen tests: When she heard nothing for months, she took matters into her own hands – typical Knef. According to her memoirs, she met the UFA film director in the canteen one day and confronted him with the fact that she had still not received an answer to her screen test. An illustrator-to-be confronts the film boss of UFA about screen tests? This apparently impressed the film boss so much that he did not forget Knef’s name so quickly.

So it happened that the young Hildegard Knef was no longer trained as an illustrator but as an actress from 1943 onwards.

Acting training in the hail of bombs

Hildegard Knef trained as an actress in the turmoil of the Second World War. Knef gained her first acting experience in the hail of bombs – theatre performances in Berlin were almost impossible in the last years of the war because the air raid alarm constantly interrupted the performances.

After the end of the war, Hildegard Knef received her first engagement at the Tribüne on Berlin’s Kurfürstendamm: with this engagement, Hildegard Knef catapulted herself to the forefront of the post-war theatre world. Germany had only a few top-class actresses to offer, most of them had long since emigrated. Actors who were famous before the war were disgraced after the end of the war and were unwanted.

During the last months of the Second World War Hildegard Knef took part in different productions, but all of them could only be seen in the cinemas after the end of the war.

Hildegard Knef’s hour had come: In the very first German film of the post-war period, The Murderers Are Among Us (1946), Hildegard Knef played the leading role and cleared numerous positive reviews: With her first major film role ever, the film critics already promoted the young actress to character actress.

Career put on hold

American film producer David O. Selznick discovered Hildegard Knef in The Murderers Are Among Us and offered the actress a Hollywood contract in the late 1940s. Which actress turns down a Hollywood contract at a young age? Knef accepted.

But what followed Knef often described in later interviews as “lost time”: although she received an attractive weekly salary, her career was put on hold. Later Hildegard Knef even suggested that her career had been deliberately put on hold in order to establish the American film industry in Europe as best as possible immediately after the end of the war and to push European film culture into the background. It is true that Hildegard Knef learned the English language during this time and met film stars such as Marlene Dietrich, who soon turned out to be a kindred spirit. In her memoirs, Knef describes how Marlene Dietrich took her under her wing as a newcomer and told her exactly how she would survive in American show business.

But: As Knef later said, it doesn’t take three years to learn English: Hildegard Knef’s first encounter with Hollywood was not exactly positive.

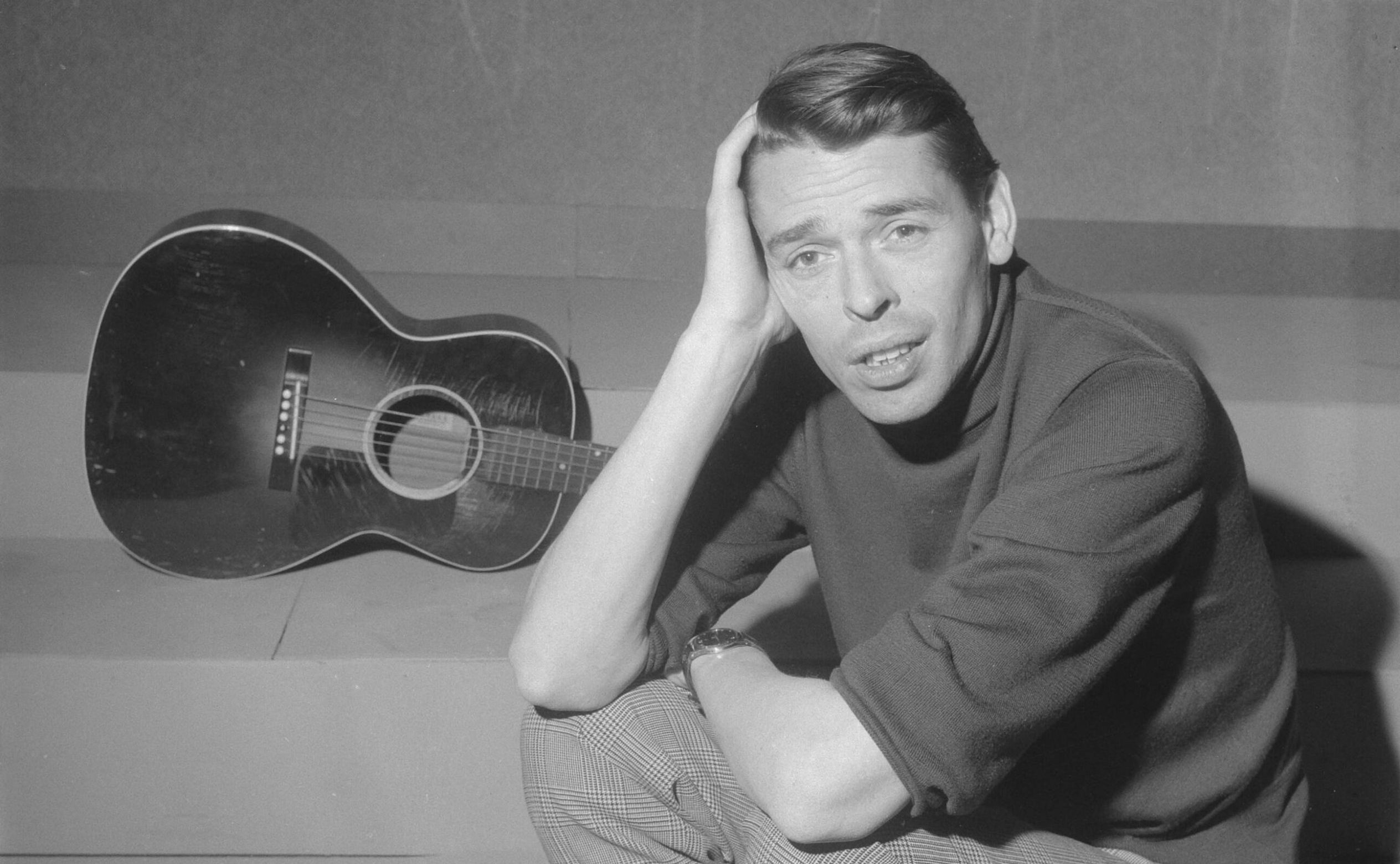

Cole Porter

After the Hollywood disappointment, Hildegard Knef returned to Germany in August 1950: she was to star in The Sinner (1951), directed by Willi Forst. Because of a short nude scene with Hildegard Knef, the film caused an international scandal, but at the same time increased Hildegard Knef’s popularity enormously. Nevertheless, it was not her big breakthrough; later Knef even expressed the opinion that Die Sünderin was her worst film from an acting point of view. In the melodrama Illusion in a Minor Key (1952), Hildegard Knef played alongside Hardy Krüger.

In the film version of the Hemingway classic of the same name, The Snows of Kilimanjaro (1952), Knef sang two Cole Porter songs. Cole Porter saw the film and was so enthusiastic about Knef that he hired her for his next Broadway production.

That Broadway production marked Knef’s international breakthrough: then, as now, it is extremely unusual for a German actor to make his Broadway debut. Hildegard Knef appeared in the Cole Porter musical Silk Stockings a total of 675 times from 1954 to 1956.

It was eight performances a week: in retrospect, Knef described this engagement as extremely exhausting, yet it formed the basis for her further fame. Marlene Dietrich, who was in New York at the same time, cooked for Knef during her Broadway engagement.

The chanson singer thundered out the lines with enormous precision and stylistic confidence.

Chanson singer

In the sixties, Hildegard Knef ventured into the genre of chanson singing: it was Hildegard Knef’s ‘second career’. In the sixties, Hildegard Knef had unprecedented success with recordings. With chansons like Er war nie ein Kavalier [He was never a cavalier], Für mich soll’s rote Rosen regnen [Let it rain red roses for me] or Von nun an ging’s bergab [From now on it went downhill], Knef celebrated great successes. With chansons like Berlin, Dein Gesicht hat Sommersprossen [Berlin, Your Face Has Freckles], Knef expressed her attachment to her hometown. No matter where she was, she was a Berlin Snout all her life.

At that time, there was no voice even remotely similar to Knef’s: it sounded slightly smoky, and the chanson singer thundered out the lines with enormous precision and stylistic confidence. Sometimes her chanson lyrics were uncomfortable, human illusions and disappointments are common themes in Knef chansons.

The fate of a generation

One could say Hildegard Knef was a real all-rounder: as if two careers as an actress and singer were not enough for her, she went one step further in the seventies and established herself as a writer. Her memoir, entitled Der geschenkte Gaul [The Gift Horse], is one of the best-known autobiographical works by a German actor. The autobiographical work is fascinating not least because of Knef’s writing style, which makes the work stand out strongly from other memoirs.

Hildegard Knef did not only have a career as an actress: fate regularly threw new obstacles in Hildegard Knef’s direction. It was inevitable for her to also establish a foothold as a chanson singer and writer. Not least because of her dramatic experiences during the Second World War, Hildegard Knef’s story was the story of an entire generation – Knef carried the story of this generation around the globe, so to speak, with her fame.

Main sources: Knef, Hildegard: “Der geschenkte Gaul” [The Gift Horse], 2009 Ullstein Paperback and an interview with Hildegard Knef from the 1960s.

Cover picture: Hildegard Knef in Zurich und St. Moritz, 1956

Picture credit: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Photographer: Metzger, Jack / Com_X-K122-001 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Deutsch

Deutsch