“There is nothing more annoying than having to put a note under every word,” Jacques Brel once claimed. It was his greatest passion and talent to write chansons. He set himself the goal of using his chansons to process feelings, to sketch people and situations, and thus to captivate the listener.

He often felt restricted by the strict rules of music and considered them an obstacle to his poetic creativity: nevertheless, a Jacques Brel chanson could not live without musical accompaniment. The chanson was his vocation.

Every beginning is difficult

It took a long time for Jacques Brel to gain recognition on the chanson scene: In his native Brussels, he began performing songs he had written himself – initially without success.

His father had intended a bourgeois life for his son Jacques Brel: At a young age, he began working in the family cardboard box factory. But Brel found this kind of life dreary and uninteresting: it was clear to him that he wanted to become an artist.

In 1953, Jacques Brel made his first recording with Philips: he had a radio presenter to thank for this opportunity. His first single, with the songs La foire and Il y a, sold no more than 200 copies, but it was enough for Philips’ artistic director to take notice and invite him to Paris.

At that time, only experienced chanson connoisseurs knew the name Jacques Brel.

New artistic home

The city of Paris, which would one day become Jacques Brel’s artistic home, initially seemed completely alien to him: Brel later said in retrospect that he had spent five years making his debut in Paris. The longed-for success as a chansonnier failed to materialize for a long time, he had to put up with insults, he was even advised to stay away from the stage and write music for other performers. Jacques Brel processed the frustration he felt at this time in various chansons.

The artistic director of Philips enabled Jacques Brel to make his first appearances in Paris theaters and helped Brel to gain a foothold in Paris. In 1954, little noticed, he performed one evening in the opening act of the Olympia. However, it would take several more years before he was able to celebrate his great success at the Olympia. At that time, only experienced chanson connoisseurs knew the name Jacques Brel.

First tour

In the summer of 1954, Jacques Brel went on his first tour: it took him to various French provincial stages, but also to his native Belgium and to North Africa.

Whenever he got out of the tour car with his musicians, the organizers were astonished: there was not a single microphone, lighting system or amplifier in the luggage. Even back then, it was extremely unusual to perform without these technical aids. For Jacques Brel, it was only in the rarest of cases that microphones or amplifiers came into question: He wanted his chansons to reach the audience unaltered and honestly – without any intermediary technology.

Stage presence

Jacques Brel realized that he loved to go on tours: Beginning in the mid-fifties, Brel made regular tours that took him mainly to the francophone part of the world.

Brel’s stage presence was anything but conventional for the time: he saw every performance as a play, and stuck to a fixed form of his performances with a beginning, climax and end. That’s why he never gave an encore, no matter how hard the audience stomped their feet: the performance was over when Brel had made that decision from a dramaturgical point of view.

The chanson Quand on n’a que l’amour became Jacques Brel’s first big record success in 1956: this success prompted numerous French chanson singers to cover the song. There are countless cover versions of this chanson – as there are of many Brel chansons. Many of his most famous chansons were written in hotel rooms at that time: Among these chansons were Amsterdam, Mathilde or Ces gens-là. Between his concerts – sometimes he gave almost three hundred concerts a year – he always had creative phases, which he used to write chansons.

Brel’s unique stage presence and his interpretation of a poetic chanson forbid any comparison.

The myth of Jacques Brel

At the end of the 1950s, Jacques Brel was one of the most sought-after French chanson artists: his countless concert appearances boosted sales of his records significantly.

In 1961, Jacques Brel had a unique opportunity: he stood in for Marlene Dietrich and gave an evening at the Olympia in Paris. There, where he had nearly perished a few years earlier as an opening act, he now celebrated one of the greatest successes of his career. Now Jacques Brel was one of France’s chanson greats and was compared to Charles Aznavour, Yves Montand or Gilbert Bécaud. But Brel’s unique stage presence and his interpretation of a poetic chanson forbid any comparison.

Meanwhile, Jacques Brel was more than a chanson singer: not only did he become a figurehead of Francophone culture, a myth grew around his person and his art.

After touring the Soviet Union, the United States, and Canada, Jacques Brel was a worldwide phenomenon. Even people who did not understand a single word of French felt captivated by Jacques Brel’s music.

In the mid-sixties, Jacques Brel was at the height of his fame: for him, this was exactly the right time to retire from the stage.

“Chanson salesman?” Not with Jacques Brel

To end up as a “chanson salesman” was the last thing Jacques Brel wanted: In 1967, Jacques Brel sang the chansons of his extensive repertoire on a stage for the last time in his life. At the beginning of the seventies, Jaques Brel devoted himself to flying: in the course of the seventies, Brel crossed the Atlantic several times. In the meantime, Brel had grown tired of society’s regulated way of life and withdrew from the public eye: he settled on the island of Hiva Oa in the southeastern Pacific and spent his twilight years there. There, for the last time in his life, he found the energy and creativity to write chansons: To record the chansons he had written in seclusion on Hiva Oa, he traveled back to Paris in August 1977.

Often copied, never reached

Jacques Brel died on October 9, 1978, barely a year after recording his last record. His grave is on Hiva Oa, not far from the memorial of the painter Paul Gauguin, who had also spent his twilight years on the island.

Often copied, never equaled: this saying applies to Jacques Brel. In the course of his career, he performed almost only his own chansons: For the musical accompaniment to his chansons, however, he relied on composers to complete his chansons with music. His collaboration with the French composers François Rauber and Gérard Jouannest had a decisive influence on Brel’s chanson style.

Jacques Brel: This name stands not least for an emotional spark that jumps from the singer to the audience and reaches the audience even if they do not know a word of French. This spark has remained until today.

Main source: Todd, Olivier: “Jacques Brel – A Life”, 1997 Achilla Press publishing

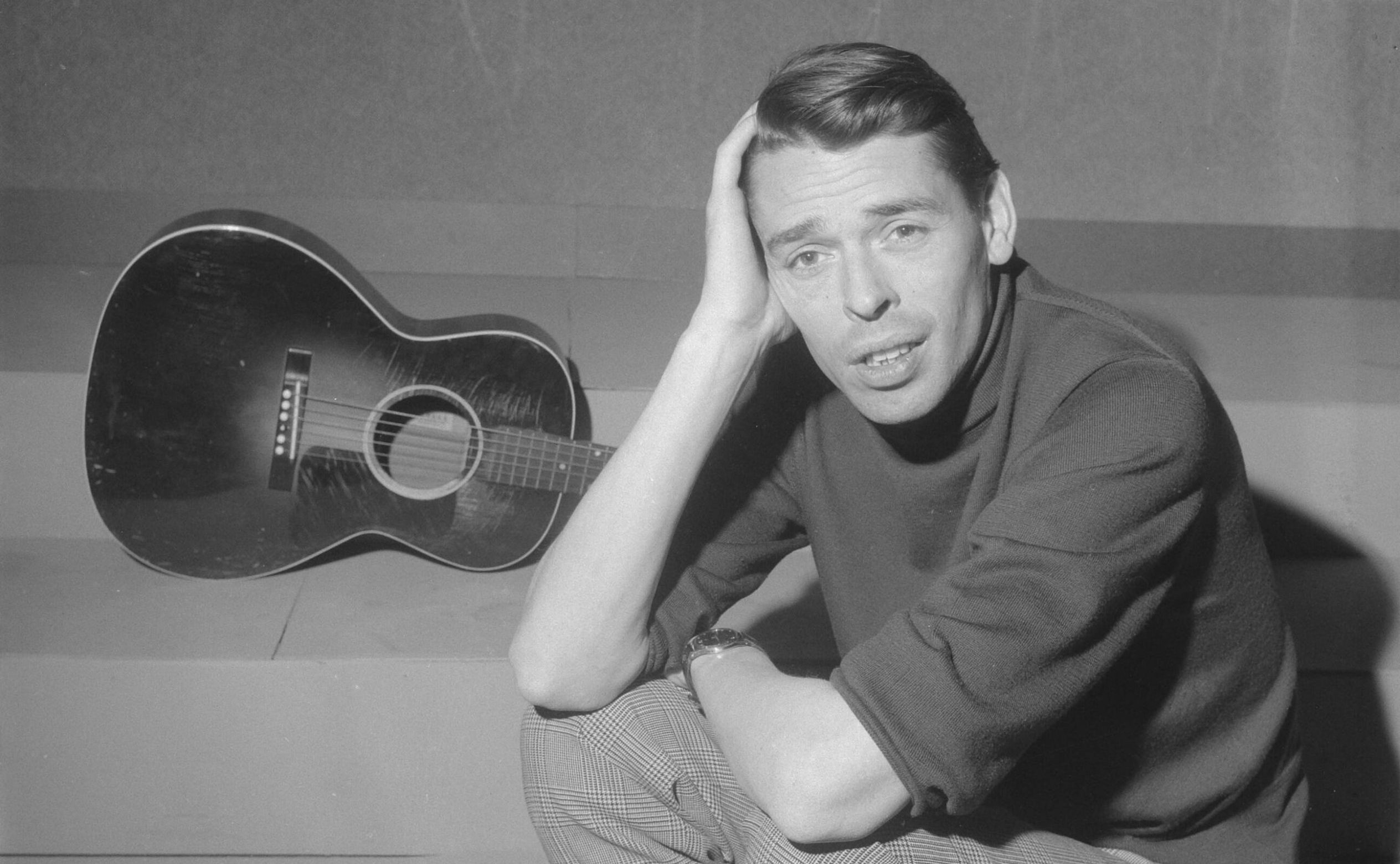

Cover picture: Jacques Brel in 1962

Image credit: Fotograaf Nijs, Jac. de / Anefo, Nationaal Archief, CC0

Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français