His career began as a ghostwriter in Berlin in the twenties: between 1927 and 1929, Wilder is said to have worked on almost fifty scripts for silent films. Had he not agreed to work as a ghostwriter at a young age, he probably would never have made it as a respected filmmaker. The talent of the young Billy Wilder was recognized, but the film industry at that time relied on well-known names to whom they gave the orders for writing scripts and screenplays. Often, however, these scripts were not actually written by the person who received the credit for them. Many colleagues from the professional environment of the young Billy Wilder never received an assignment for which they were named in the credits of a film – it is hard to figure out how many great writing talents at the time never got beyond the status of ghostwriter.

But Billy Wilder was to succeed in asserting himself as a “serious” screenwriter and, later, director…

Emil and the Detectives

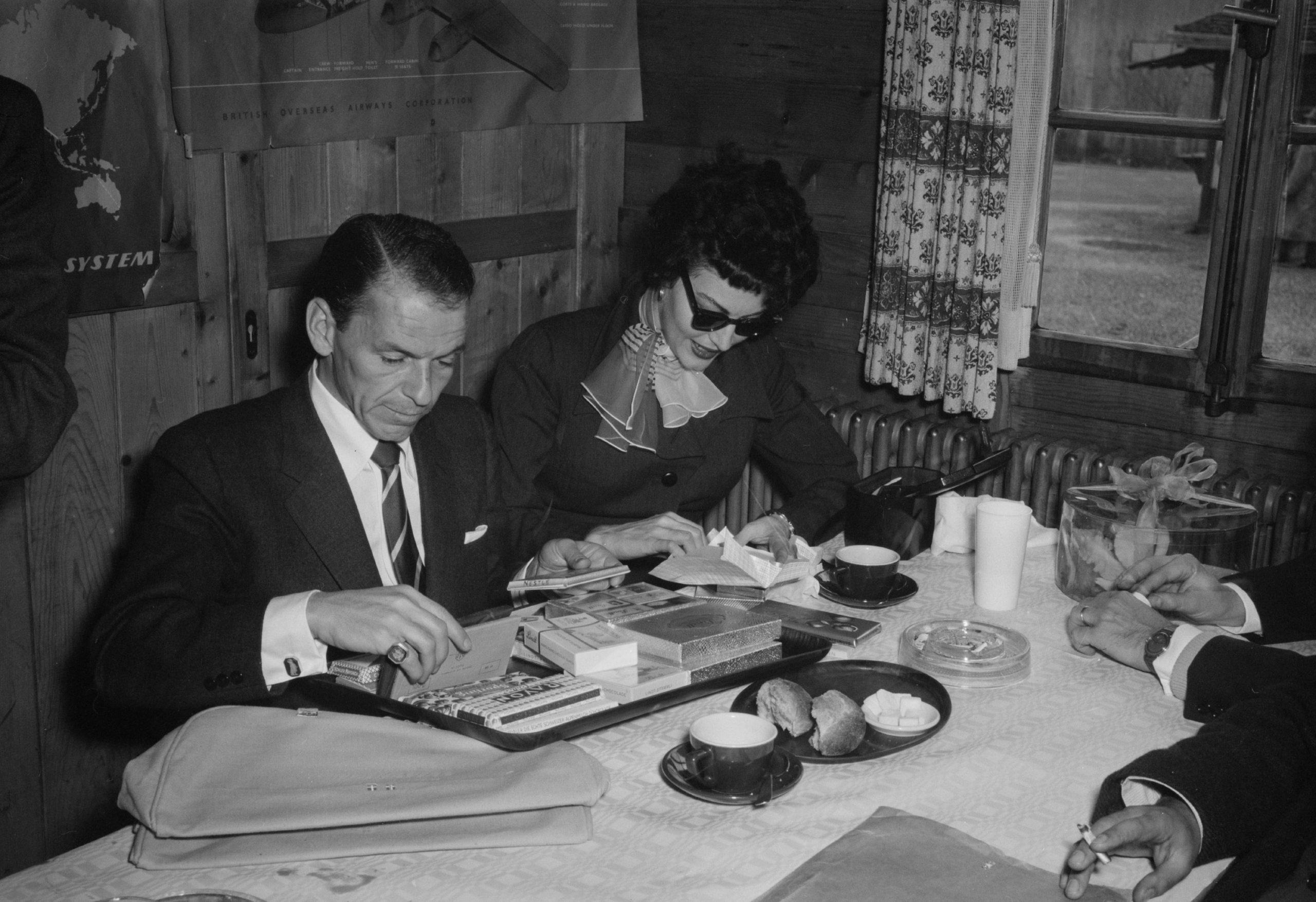

During his time in Berlin in the twenties, Billy Wilder met personalities such as Marlene Dietrich, who would later star in two of his films.

The fact that Wilder later frequently made films around the subject of journalism and reporting had a reason: after studying law for a year at the University of Vienna, Wilder broke off his studies to work as a sports reporter for a Viennese newspaper. A short time later, a newspaper in Berlin took an interest in the young writing talent: the writing experience that the young Wilder gained in Berlin in the late twenties would later prove to be very valuable.

In 1930, a way out of the professional existence as a ghostwriter presented itself to the young Wilder: on the film Menschen am Sonntag (“People on Sunday“, 1930), Billy Wilder was credited as a screenwriter for the first time. The film was made on a very low budget: One of the assisting cinematographers was Fred Zinnemann, who later pursued a very successful career as a director in Hollywood himself. In 1931, Wilder co-wrote the screenplay for the film version of Emil and the Detectives (1931) with the very successful author of children’s books Erich Kästner.

In the French film Mauvaise Graine (1934), Wilder was named as co-director for the first time.

First directorial work

Originally, Billy Wilder was not a director at all, but a screenwriter: The fact that Wilder directed at all was initially a stopgap measure. After Billy Wilder emigrated to France in 1933, the young screenwriter practically started from scratch: At this point, he had established a reputation in Berlin, but as a result of the regime change, the young Wilder considered it inevitable to leave Germany immediately. In the French film Mauvaise Graine (1934), Wilder was named as co-director for the first time. Billy Wilder took the post of co-director mainly for financial reasons, as hiring a director would have blown the very meager budget of the independently produced film.

In January 1934, Billy Wilder left Europe: aboard the Aquitania, he traveled to New York. Joe May, an acquaintance of Wilder and one of the pioneers of German cinema, had meanwhile emigrated to Hollywood: In his capacity as producer at Columbia Pictures, May was able to bring his friend Wilder to Hollywood to offer him career opportunities. Billy was already expected in New York by his older brother: he had emigrated to the United States some time before and had built up a successful business.

“Then you better write some good screenplays…”

Arriving in Hollywood, Wilder was initially faced with a problem: He only knew German and French. Both languages, however, played virtually no role in the day-to-day operations of Hollywood – Wilder is said to have taught himself English by listening to radio broadcasts of baseball games and visiting the movie theater.

For the time being, the language barrier prevented Billy Wilder from gaining a foothold in Hollywood: His six-month contract with Columbia Pictures expired, and with it his temporary residency permit for the United States. As a result, Wilder went to Mexico to apply for a visa for the U.S. from there – the quota for European immigrants was already saturated. The consul in charge was critical and asked Wilder how he planned to make a living. Wilder replied firmly that he planned to write screenplays. The consul is said to have been a movie buff himself and discharged Wilder with a visa for the United States, accompanied by the words, “Then you’d better write some good screenplays…”

At Paramount, numerous exiles were under contract at that time.

Professional marriage

After canvassing various Hollywood studios, Billy Wilder finally landed a contract with Paramount Pictures in 1936: At Paramount, numerous exiles were under contract at that time: That’s why the building on the Paramount lot where the writers were housed was christened the “Tower of Babel.”

In 1939 Billy Wilder was involved in writing the screenplay for the Greta Garbo film Ninotchka (1939): He co-wrote the screenplay with Charles Brackett and Walter Reisch. Charles Brackett and Billy Wilder wrote numerous screenplays together in the thirties and early forties – Paramount Pictures encouraged the partnership between the two writers.

In 1942, Brackett and Wilder, both filmmakers, agreed on a new arrangement: Wilder would direct and Brackett would produce. Wilder once described this collaboration as a kind of “professional marriage” – for such a professional cooperation to bear fruit, many factors had to be right.

The Major and the Minor (1942) was Billy Wilder’s first directorial effort in Hollywood: Ginger Rogers and Ray Milland played the leading roles, Charles Brackett wrote the screenplay together with Wilder.

Sunset Boulevard

In the forties Billy Wilder realized numerous other high-profile film projects: Of particular note are the film projects Five Graves to Cairo (1943) and A Foreign Affair (1948), starring Marlene Dietrich. A Foreign Affair is set in devastated postwar Berlin and captures the atmosphere as it prevailed at the time like few other films of the era. The film musical The Emperor Waltz [Ich küsse Ihre Hand, Madame, 1948], realized by Wilder, starred Bing Crosby.

Billy Wilder started the 1950s with one of the highest-profile film projects of his entire career: Sunset Boulevard (1950) saw silent film star Gloria Swanson make her big comeback. The film deals with the myth of the Hollywood dream factory in a critical and sarcastic way; Wilder directed one of Hollywood’s greatest masterpieces with this film. Another important film project followed with Ace in the Hole (1951), starring Kirk Douglas. For the film Ace in the Hole, which takes a very critical look at sensational journalism, Wilder drew on his many years of experience as a journalist in Berlin in the twenties.

Monroe owed much of her image to the directorial work of Billy Wilder.

Screen legends

The filming of Witness for the Prosecution (1957) was the second time Billy Wilder directed a film starring Marlene Dietrich. The courtroom drama knows how to keep the viewer guessing about the exact course of events until the end of the plot, and keeps the viewer riveted to the cinema seat.

The two collaborations with Marilyn Monroe, The Seven Year Itch (1955) and Some Like it Hot (1959), have remained in the collective memory. Monroe owed much of her image to the directorial work of Billy Wilder: Under his direction, the unique actress climbed to the peak of her Hollywood career.

The comedy Some Like It Hot, which assembled Marilyn Monroe, Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis in the leading roles, is still considered a prime example of the genre.

Director of the century

Billy Wilder immortalized himself with his directorial works and is one of the most influential directors of the 20th century: apparently Wilder took to heart the advice of that consul who issued him a visa to the U.S. in the mid-1930s (“Then you’d better write some good screenplays…”). Wilder wrote more than a few “good screenplays” – and he directed some of the most impressive film works of the last century. He instructed screen legends Marlene Dietrich and Marilyn Monroe, and in particular helped Marlene Dietrich to a successful postwar career through the two films A Foreign Affair and Witness for the Prosecution. Only a few directors understood how to perfectly stage screen legends like Marlene Dietrich – Billy Wilder was one of them.

Billy Wilder had an unprecedented career: At the beginning of his career, it was not even clear whether he would ever get beyond the status of a ghostwriter. He probably never expected that he would one day be considered a director of the century.

Cover picture: © Simon von Ludwig

Main source: Phillips, Gene D.: Some Like It Wilder – The Life and Controversial Films of Billy Wilder, 2010 The University Press of Kentucky

Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français