It was not a singing teacher, nor an opera director nor even a family member who discovered the extraordinary vocal talent of the Sicilian-born Giuseppe di Stefano: the opera-loving law student Danilo Fois is considered Giuseppe di Stefano’s discoverer. When the di Stefano family moved to Milan in 1937, the young Giuseppe met Danilo Fois for the first time – the two became friends and Fois recognised the enormous potential in his friend Giuseppe and motivated him to pursue a professional singing career. The two often played cards together – the winner of a round not only got money, he also got to perform a singing part. When Fois, who is said to have possessed a brilliant falsetto voice, once performed La donna è mobile from Rigoletto, di Stefano is said to have joined in at the end and sang the last, extremely high, note with an impressive tenor voice. From then on, there was no doubt: if the law student Danilo Fois could not live out his vocal talent professionally, at least his friend di Stefano would have to do so with his brilliant tenor voice…

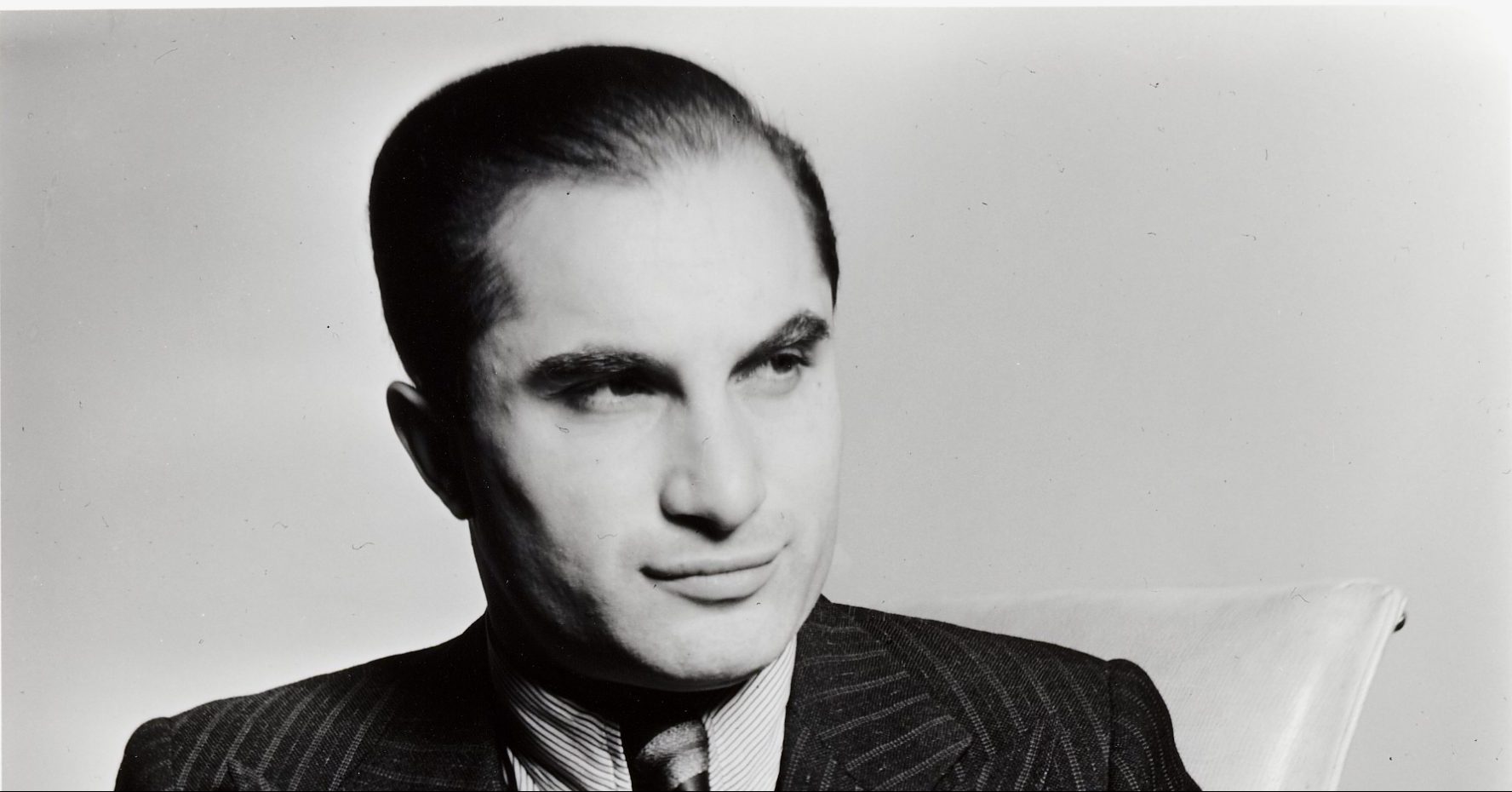

Luigi Montesanto

Following the advice of Danilo Fois, the young di Stefano took part in various singing competitions, from which the young tenor usually emerged very successful: Through various singing gigs in pubs and snack bars, di Stefano soon met people who had enough means to support a promising young singer: Di Stefano’s family would not have been able to have his singing talent trained.

When Giuseppe di Stefano decided to start professional vocal training, he met another person whose acquaintance was indispensable for his progress as an opera singer: the baritone Luigi Montesanto (1887 – 1954) took over the vocal training of the young di Stefano from then on and later also became his manager. In the course of his career, Montesanto had already appeared on stage alongside Enrico Caruso and looked back on an international career as an opera singer in his early forties. The fact that Montesanto was di Stefano’s teacher later opened up numerous opportunities for the young opera singer in the opera world: if di Stefano had not first met the opera-loving law student Danilo Fois in his early life and later the baritone Luigi Montesanto, the sound of his voice might never have crossed the borders of the city of Milan.

Fois had the idea of di Stefano’s career – Montesanto implemented this idea by teaching the young tenor accordingly.

In a way, his unique tenor voice had saved his life.

Activity in Switzerland

But before Giuseppe di Stefano could seriously embark on his career as an opera singer, world history threw a spanner in the works: during the Second World War, Giuseppe di Stefano was drafted to serve in an infantry regiment. In this situation, too, the budding opera tenor was very lucky:

When the regiment was ordered to support the German troops in the Russian campaign in 1941, the officer ordered him to stay in Italy. “(…) As a tenor, you can be useful to our country one day – yes, I am sure!”, the commanding officer justified his decision. According to the reports, no one from di Stefano’s regiment returned from Russia. In a way, his unique tenor voice had saved his life.

In the turmoil of the Second World War, Giuseppe di Stefano was sent to an internment camp in Switzerland: but even there, di Stefano soon attracted attention with his singing voice and was taken out of the internment camp by Edoardo Moser, the artistic director of Radio Lausanne. At Radio Lausanne, Giuseppe di Stefano took part in a total of three opera performances in September 1944: These included L’elisir d’amore (Donizetti), Il Tabarro (Puccini) and La cambiale di matrimonio (Rossini). The Swiss conductor Otto Ackermann, who had advised the opera singer Max Lichtegg a few years earlier when he was starting his career, conducted all three performances.

Debut and break with La Scala

After the Second World War was over, di Stefano returned to Milan: there he initially faced existential difficulties again, but he also returned to his teacher Montesanto, who agreed to continue his training and act as his impresario. After his return to Milan, Giuseppe di Stefano worked his way up to the Teatro alla Scala, Italy’s most important opera house, in a very short time: Without question, the connections of the opera baritone Luigi Montesanto opened countless doors for him in the opera world. As early as the end of 1946, di Stefano was in contact with Tullio Serafin, the artistic director of Teatro alla Scala: at the beginning of 1947, the two then met at La Scala in Milan and Serafin engaged him for a production of Manon (Massenet) in March 1947. At that time, Tullio Serafin enjoyed enormous prestige in the Italian opera world: a tenor who was recognised by him as a great talent usually had the doors to a world career open to him. In the following years, di Stefano received offers for another career at La Scala, but he decided in favour of an international career. When di Stefano received an offer for an engagement at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in the spring of 1948, he broke his contract with La Scala in favour of the Met engagement. For this break with La Scala, he was condemned by those responsible there – but di Stefano initially preferred an intermezzo at the Metropolitan Opera. However, the break with La Scala was by no means to last forever: Giuseppe di Stefano wanted to continue his artistic education before returning to his home in Milan…

It was no easy task for an opera singer to hold his own next to the vocal force of nature of Maria Callas.

First to the Met, then back to Italy again

Giuseppe di Stefano first appeared alongside Maria Callas in La Traviata (Verdi) at the São Paulo Opera in September 1951: Di Stefano’s singing career was not limited to the Metropolitan Opera in New York, he was equally in demand in Mexico as in Rio de Janeiro in the early fifties. Tullio Serafin conducted that production, with Tito Gobbi as Germont père. Who could have guessed back then, in September 1951, that this would be the beginning of one of the most legendary operatic duos in opera history?

After several successful seasons at the Metropolitan Opera, Giuseppe di Stefano could gradually think about returning to his native Italy. Only after several seasons at the Met did di Stefano begin to think of claiming his place there – besides, for any Italian opera singer, a success at La Scala is usually far more significant than any success at the Metropolitan Opera, no matter how long it lasts. After Maria Callas returned from her engagement in Mexico, she lobbied for di Stefano’s engagement at La Scala in Milan: At La Scala, both opera singers experienced a golden period in their careers in the fifties: it was also a time when Maria Callas was entrusted with almost all season openings at La Scala. It was no easy task for an opera singer to hold his own next to the vocal force of nature of Maria Callas – Giuseppe di Stefano mastered it, for example in a new production of La Traviata (Teatro alla Scala, 1955) alongside Maria Callas. The radio recording made on the occasion of this new production enjoys legendary status today. Until 1957 di Stefano recorded a total of ten operas with Maria Callas. The vocal harmony between the two was unique.

Concerts with Maria Callas – He gave a piece of his voice

In later years, Giuseppe di Stefano went on tour together with Maria Callas: the 1973/1974 tour, which both singers embarked on together and was generally regarded as Maria Callas’ “farewell tour”, permanently cemented the legendary status of both opera singers. On stage, Callas and di Stefano were rarely together – of her more than five hundred opera evenings, Callas spent not even fifty of them on stage with Giuseppe di Stefano. However, it was not the quantity but the quality of those performances that mattered: Thanks to the numerous opera recordings with both singers, posterity can guess what a harmonious duo both singers must have been on the opera stage. The Lucia di Lammermoor production conducted by Herbert von Karajan, which made guest appearances at La Scala in 1954, in Berlin in 1955 and in Vienna in 1956, also played a significant role in the legendary status that the opera duo Callas-di Stefano enjoys.

It is often said that di Stefano was “wasteful” with his voice and that his brilliant tenor voice with enormous potential quickly “burned up”. Indeed, in the early fifties he strained his voice enormously and used unorthodox singing techniques, but one thing is beyond question: Giuseppe di Stefano sang his whole life in the service of opera. He dedicated a piece of his voice to opera in the course of his career.

Cover picture: Giuseppe di Stefano (r.) in 1973 with Maria Callas at Amsterdam Schiphol Airport, Fotograaf Onbekend / Anefo, Nationaal Archief, CC0

Main source: Semrau, Thomas: Alles oder nichts. [All or nothing.] Giuseppe di Stefano, 2002 Residenz Publishing House Vienna

Deutsch

Deutsch