He had a major influence on the development of modern American stage music: Kurt Weill was one of the most important composers of the first half of the 20th century.

Kurt Weill worked in an era when the demands on music were changing: from now on, the task of music was to be short, immediate and easily accessible. The era of aestheticism was over – the days of the motto L’art pour l’art, art for art’s sake, were over.

A new epoch of the arts was in the offing: Although the epoch term New Objectivity is mostly used for painting, there was a new music movement in Germany in the 1920s under the same name. When a large part of the masses were introduced to music for the first time via the then new medium of radio, the basic conditions of the musical arts changed…

Music became more immediate, more tangible and more accessible to many people.

Music becomes more tangible

What could previously only be experienced in a concert hall or opera house was now booming out of the gramophone or radio speakers in many people’s homes and flats: music became more immediate, more tangible and more accessible to many people. This created new demands that music had to meet.

In the 1920s, Weill formulated that the “traditional form of opera” created by composers like Strauss, Wagner and their cultural heirs had come to an end.

Kurt Weill’s first compositions were not written for the stage: immediately after his training at the Berlin Academy of the Arts, he wrote orchestral works, chamber music and piano pieces.

But Weill realised that he could not fulfil his ambitions with these compositions: His interest lay rather in the realisation of concise and formal brevity, which was later reflected in his stage works. This concise brevity can also be found in Weill’s first works, which were almost all operas in a single act.

Georg Kaiser

During his time in Berlin, Weill met the expressionist playwright Georg Kaiser (1878 –1945): From Kaiser, Weill received numerous suggestions for his work as a stage composer.

With the modern theatre of the early 20th century, Kurt Weill had found his niche: He saw it as his task to accompany theatre and opera into the modern age: The 20th century marked a caesura in the history of theatre and opera.

Both art forms were now accessible to a much broader mass than in the 19th century.

The playwright Georg Kaiser not only provided the inspiration for many of Weill’s works, he also wrote the libretti for numerous Weill works, including Der Silbersee [The Silver Lake, premiered in Berlin in 1933], Weill’s last opera before leaving Germany.

Bertolt Brecht

Kurt Weill is still known today for his collaboration with one of the most influential playwrights of the 20th century: Bertolt Brecht. In the spring of 1927, in the midst of the heyday of Weimar culture, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill met: the two met not least because they were already regarded as reformers of the theatre.

Bertolt Brecht was an author, not a composer: Brecht needed someone at his side who could musically realise his vision of the new form of theatre.

Kurt Weill seemed the ideal partner for this: Weill worked with Brecht on the musical realisation of operas such as The Threepenny Opera (world premiere 1928) or Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny (premiere 1930). Thanks to Weill’s classical training, the playwright Brecht was able to implement his progressive ideas of theatre and opera. Brecht not only had progressive ideas about art: his progressive ideas and ideals about social coexistence were put into a musical form by Kurt Weill that the audience could relate to.

The Weill Chanson

In Berlin in the 1920s, Kurt Weill met the dancer, actress and chansonnière Lotte Lenya, whom some may recognise because she played the role of the ex-KGB officer Rosa Klebb in the 1963 James Bond movie From Russia With Love.

Kurt Weill emigrated together with Lotte Enya first to France in 1933 and two years later to the United States: Lenya later became known in the United States as a high-profile interpreter of Weill chansons.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Weill chanson almost formed a musical genre of its own: every distinguished German-speaking chanson artist usually dedicated an entire vinyl record to Weill chansons, including Greta Keller (Greta Keller sings Kurt Weill, 1953).

Kurt Weill’s late work contains crucial stages in American musical history.

Late work – still important today

When Weill emigrated to the United States in 1935, he initially suffered a culture shock: living conditions were completely different from those in Europe and people followed a different zeitgeist. In the late thirties and forties, no form of musical theatre was as popular in the USA as the musical: a form of music that a European like Kurt Weill could not relate to at first.

But Kurt Weill was adaptable: he set himself the goal of creating an “American folk opera”. He was to succeed in this with his musicals, which he soon began to write.

Until his death in 1950, Kurt Weill wrote numerous musicals for the American stages, including Lady in the Dark (1941) and One Touch of Venus (1943). He also wrote operas, including Street Scene (1947) and Down in the Valley (1948). Although it is hardly ever realised today: Kurt Weill’s late work contains crucial stages in American musical history, which in turn has exerted a decisive influence in Europe for decades. Thus, the work of composer Kurt Weill has hardly lost any of its influence since his death in 1950, even if his creative achievement is rarely emphasised. This has not least to do with the fact that Weill works were not performed in his home country until 1945.

“Christa, you have to sing Lieder in that vein too.”

Weill’s chansons developed from ballads and cabaret chansons. The composer was able to combine these styles with the jazz movement that was just emerging: In the 1920s, when Kurt Weill wrote some of his greatest works, the careers of later highly influential jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong were still in their infancy. Nevertheless, countless stylistic elements of jazz spilled over to Europe as early as the 1920s.

The opera soprano Christa Ludwig writes in her memoirs that the influential British record producer Walter Legge once played her a Lotte Lenya vinyl record of Weill songs: Ludwig was still at the beginning of her career and was advised by Legge: “Christa, you have to sing Lieder in that vein too.”

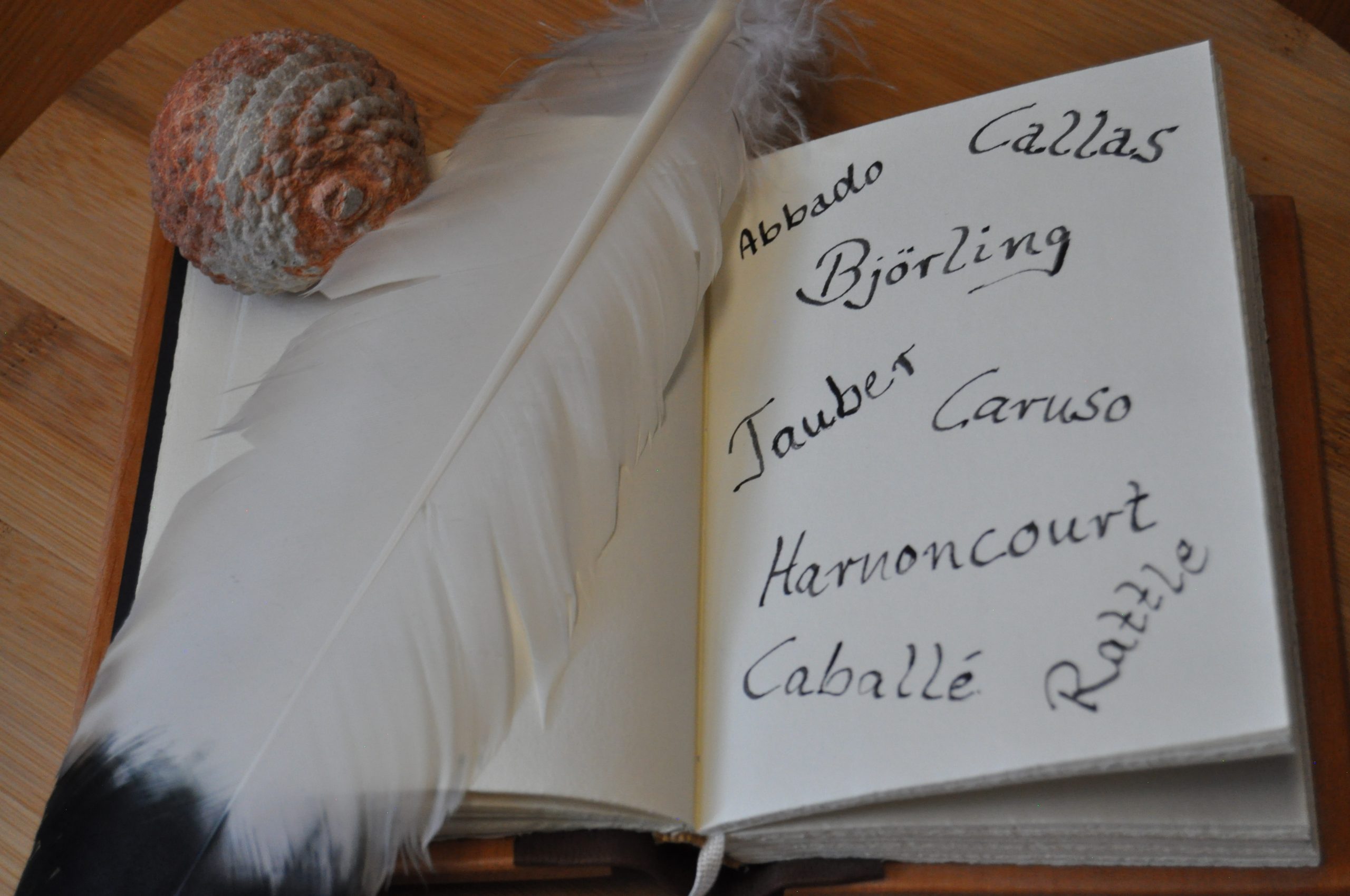

Weill chansons are considered the measure of all things as far as vocal expression is concerned. Only the most expressive singers are able to interpret a Weill chanson in all its fullness.

Cover picture: © Simon von Ludwig

Main sources:

- Oper, Operette, Konzert – Komponisten und ihre Werke [Opera, Operetta, Concert – Componists and their works], Mosaik publishing house 1979

- Haas, Michael: Forbidden Music – The Jewish Composers Banned By The Nazis, 2013 Yale University Press

- Ludwig, Christa: … und ich wäre so gern Primadonna gewesen – Erinnerungen [In My Own Voice], 1994 Henschel Verlag

Deutsch

Deutsch