“Dmitri is a good name. We’ll call him Dmitri,” the priest present at Dmitri Shostakovich’s baptism is said to have decided. His parents actually wanted to call him Jarosław – but this name seemed too unusual for the priest and so he decided to christen the baby Dmitri.

At the age of 19, Shostakovich composed his Symphony No. 1: one would think that a composer and conductor like him would have harboured a fascination for music from an early age. However, Dmitri Shostakovich did not have the typical childhood of a musical genius: although he undoubtedly grew up in a musical environment, Shostakovich’s childhood was typical for the time.

Dmitri’s parents did not necessarily want him to become a musician: Nonetheless, his mother trained him on the piano – however, she did not use any musical methods as a guide, but her intuition and musical feeling alone. Biographers today agree that it was precisely this relative simplicity of his mother’s training that formed the basis for Shostakovich’s later mastery of the piano.

One of the most influential personalities in Shostakovich’s education was the director of the conservatory, Alexander Glazunov.

October Revolution and studies

“I experienced the October Revolution in the streets,” Shostakovich later said about his childhood and youth: the circumstances of his time undoubtedly left their mark on him. But regardless of the new circumstances that arose in the wake of the October Revolution, the Shostakovichs did not abandon music: On the contrary, music was more than ever at the centre of events. Initially, it was Dmitri Shostakovich’s talent on the piano that attracted the most attention: although his talent as a composer was recognised, the focus of his training was initially on the piano.

However, it was not long before Shostakovich’s talent as a composer was also recognised: From 1919, Dmitri Shostakovich not only studied piano with the pianist Leonid Nikolayev, but also composition with the composer Maximilian Steinberg. One of the most influential personalities in Shostakovich’s education was the director of the conservatory, Alexander Glazunov. Although Shostakovich was never taught directly by Glazunov, the director supported the young composer, even though Glazunov was generally extremely critical of modern music. But he knew that the future would not belong to him, but to composers like Shostakovich.

Silent film pianist and Symphony No. 1

In 1922, the young composer was struck by a heavy blow of fate: his father died of pneumonia – as a result, the family found themselves in financial difficulties. In order to support himself and his family, Shostakovich began working as a silent film pianist – he played the background music for silent films on the piano live in the cinema. This activity explains Shostakovich’s lifelong penchant for film music – yet for him, working as a silent film pianist was nothing more than a means of supporting his family: for him, “real music” took place in the concert hall. Nevertheless, working as a silent film pianist was not necessarily easy: among other things, improvisation on the piano was part of his work. His work in silent film cinemas took up almost all of Shostakovich’s time and kept him from creating musical works for several years.

Dmitri Shostakovich completed his composition studies in 1926 with the composition of his First Symphony, which was premiered on 12 May 1926. This I. Symphony immediately made the 20-year-old composer internationally famous: Among others, the work was performed shortly afterwards by conductor Bruno Walter in Berlin, and it was not long before the work also reached the United States – it was played in Philadelphia and in New York. This meant that Shostakovich enjoyed international fame within a very short space of time. By the time Arturo Toscanini played the work for the first time in 1931, Shostakovich’s First Symphony had entered the world repertoire and is still one of the most frequently performed pieces by Shostakovich today.

“Soviet jazz”

In the mid-1930s, Dmitri Shostakovich composed one of his most famous works to date: the Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 1 was the result of Shostakovich’s involvement in the Soviet Union’s so-called Jazz Commission, whose aim was to help a Soviet form of jazz to flourish. The intention was to create an ideological counterpart to the then emerging American jazz – Shostakovich knew better than anyone how to combine classical music with easily accessible jazz music in his suite for jazz orchestra.

In his jazz suite, Shostakovich used, among other things, the improvisational experience he had gained as a silent film pianist: his task was to take up the typical stylistic elements of jazz, but he had to process them in such a way that one would not get the idea that “Soviet jazz” had anything in common with its US counterpart, except the name. Without question, the creation of “Soviet jazz” was an important concern for those in power: on the one hand, Shostakovich proved to be a loyal musician to those in power, but on the other hand, his entire artistic output was overshadowed by the fear of falling out of favour and being executed. Shostakovich therefore automatically maintained a certain distance from the ruling system, whose dark sides he knew very well.

It is not possible to say exactly when the Suite for Variety Orchestra was composed, but it is thought to date from the second half of the 1950s.

“Waiting for the execution”

When one thinks of the work of Dmitri Shostakovich today, his Suite for Variety Orchestra comes to mind first and foremost: this Suite for Variety Orchestra is often mistakenly equated with Shostakovich’s 2nd Suite for Jazz Orchestra, but Shostakovich’s Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 2 is an independent work that he composed in 1938 and was considered lost after the Second World War. For this reason, Shostakovich’s Suite for Variety Orchestra was referred to as Suite for Jazz Orchestra No. 2 until 1999.

Waltz No. 2 from Shostakovich’s Suite for Variety Orchestra in particular enjoys great fame to this day: Waltz No. 2 is often performed separately from the suite and is a component of numerous works of film music. It is not possible to say exactly when the Suite for Variety Orchestra was composed, but it is thought to date from the second half of the 1950s.

Today, Dmitri Shostakovich is regarded as one of the most accomplished and influential Russian composers and pianists of the 20th century: his musical output spanned 15 symphonies and just as many works for violin and violin cello. Shostakovich’s life and artistic work were characterised by the external circumstances of his time. In his memoirs, he wrote: “Waiting for execution is one of the themes that have tormented me throughout my life; much of my music speaks of it.”

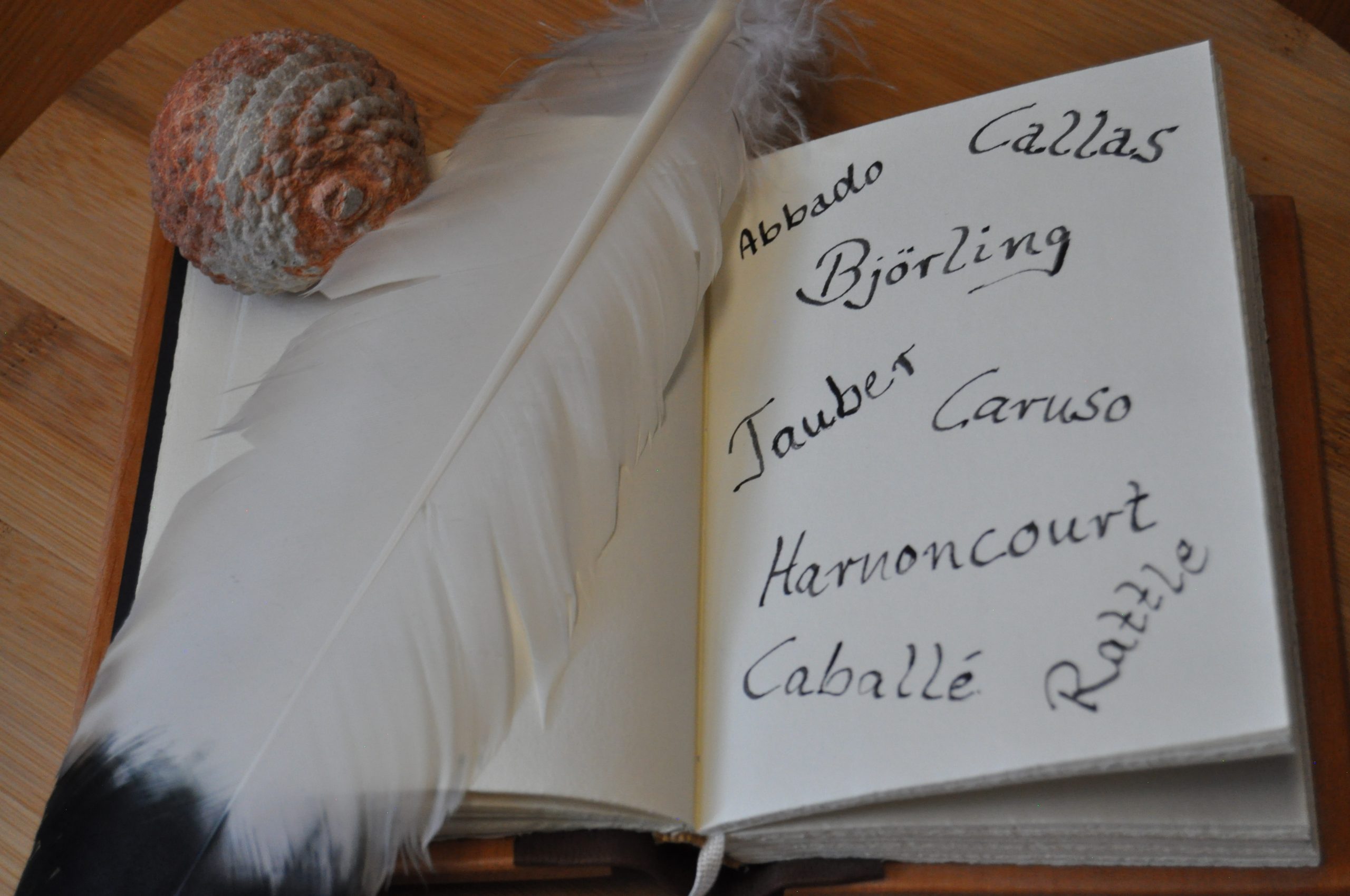

Musical bridge builder

But the feared execution never took place: Shostakovich died on 9 August 1975 from ailments that had accompanied him from a young age. Just as in his musical legacy, which undoubtedly built bridges between classical music and popular music, in his life he mastered the balancing act between forced loyalty to those in power and the ideals of his common sense. Shostakovich can be seen as a musical bridge-builder who not only advanced classical music artistically, but also helped classical music to make the leap into the modern music world, particularly with his Suites for Jazz Orchestra and his Suite for Variety Orchestra.

Main sources: Meyer, Krzysztof: Schostakowitsch – Sein Leben, sein Werk, seine Zeit [His Life, His Work, His Time], 2015 Schott Music and his biography via schostakowitsch.de.

Cover picture: © Simon von Ludwig

Deutsch

Deutsch