At the age of thirteen, the young Hans Albers is said to have scribbled his name all over the wallpaper of his childhood bedroom: When his father, owner of a large slaughterhouse in Hamburg, got wind that his young son was secretly taking acting lessons, he banished his son to Frankfurt. There he went to work during the day as a temp in a silk company – but his dream of acting was not lost among all the silk yarns.

And so it was that Hans Albers appeared on stage for the first time in 1911 in the comedy Der zerbrochene Krug (The Broken Jug). Certainly, he did not play a role that was significant for the course of the plot, but it was nevertheless his entry into the world of theater. His first stage appearance was followed by an engagement on a provincial stage in Bad Schandau in Saxony: it was on provincial stages that the young Hans Albers learned his craft.

A “misfortune”? Far from it.

In his younger years, Hans Albers faced strong headwinds from critics: some critics even went so far as to call the young Hans Albers a “misfortune.” But Albers was not deterred and put the criticism behind him: acting was his calling, of that he was sure.

When World War I began, it was not in his interest to become a war hero: In 1915, the young Albers was initially transferred to Saarbrücken before being taken to Wiesbaden because of a wound. Hardly had his injury healed and he was back on stage: Hans Albers appeared in comedy, farces and operettas at the Residenz Theater in Wiesbaden. The end of the First World War did not mean the end of the film industry – the demand for films was higher than ever. The advice circulated among actors at the time was to give Berlin a wide berth – the first films shot in Berlin after World War I were not exactly promising for a theater actor playing roles with depth.

For Albers, the emerging film and theater scene of Berlin after World War I was the chance par excellence to prove himself as an actor.

Cinema was young

Hans Albers saw things quite differently: for him, the emerging film and theater scene of Berlin after World War I was the chance par excellence to prove himself as an actor. In Berlin, Albers met the soprano Claire Dux, who was celebrated at the time as the prima donna of the Berlin State Opera: The two fell in love, and for Albers it was possible for the first time to approach more important engagements thanks to his connection with Dux. Whereas he had previously only been a laughing stock from the provinces, the young Albers was now taken more seriously in the capital.

What was the film landscape like in Berlin shortly after the First World War? There were dozens of production companies founded by speculators to make a quick buck by filming dime novels. Many films were shot with a shooting time of less than a week – including the first film in which Hans Albers starred in 1917.

By the end of the twenties, Hans Albers had acted in over a hundred silent films: “He earned well, could afford a room in the Hotel Adlon from the mid-twenties, showed up at the six-day races and boxing events, and was sometimes in the gossip columns of the capital, but he was still nothing more than a snazzy provincial ‘Heini’,” wrote Hans-Christoph Blumenberg in his biography of the actor at this time. Would Hans Albers ever become more than a “snazzy provincial ‚Heini'”? In the meantime, he knew enough about the world of film to continuously work on his image…

The Roaring Twenties

In 1929, Hans Albers starred in Die Nacht gehört uns (The Night Belongs to Us), one of the first German talkies: For an actor who had previously appeared exclusively in silent films, the transition from silent to talkies was a major challenge.

For Hans Albers, this was no problem: with the advent of the talkies, Albers’ career really took off.

In the early thirties, the myth of Hans Albers, as it is still known today, was born: In addition, Albers performed songs particularly frequently in his films – if Albers sang a song in a new film, one could be sure that everyone soon knew the new Hans Albers song.

His strength at that time lay in the “unabashed naturalness” of his acting, as Hans-Christoph Blumenberg describes in his biography: At the end of the twenties, Hans Albers threw off all the shackles that had been put on him by acting in the theater. Thus Albers was a born revue and operetta actor. Albers completely cast off the affectation that many theater actors were accused of at the time and focused on natural, realistic acting. Moreover, the talkies offered a unique opportunity for the actor to become known to an audience that could not regularly attend revues in the Berlin of the Roaring Twenties.

In the early thirties, he was a sought-after actor.

UFA Studios

Hans Albers starred in the tragicomedy Der blaue Engel [The Blue Angel, 1930], directed by Josef von Sternberg: Marlene Dietrich became a celebrated star with this film, and she left for America on the very night of the German premiere.

Hans Albers played a supporting role in The Blue Angel: at the time, this was unusual, as Albers was by now used to playing the lead. Rumor has it that one of the main actors, Emil Jannings, lobbied to have crucial scenes with Hans Albers cut out of the final version of the film. Such a thing, however, could not harm the actor Albers: In the early thirties, he was a sought-after actor who no longer had to worry about theater and film engagements. With the UFA studios, Hans Albers celebrated great film successes in the early thirties, including FP. 1 antwortet nicht (FP.1 does not answer, 1932): The film songs Flieger, grüß’ mir die Sonne (“Airman, greet the sun for me“) and Ganz dahinten, wo der Leuchtturm steht (“Way over there, where the lighthouse stands”) were no less great successes.

Old times

In the thirties and forties Hans Albers was involved in numerous film projects: Hans Albers managed to stay largely under the radar of those in charge in the totalitarian Nazi system. The Propaganda Ministry regularly observed with suspicion that Hans Albers did not fully submit to the system – but at the same time they knew that they were dependent on an actor of Hans Albers’ caliber. “The totalitarian system has blind spots,” formulates Hans-Christoph Blumenberg in his biography of Albers: for Albers, the period from 1933 to 1945 was certainly not an easy time, yet – due to his popularity – he could afford not to be one hundred percent obedient to the Nazi line compared to other actors.

Shortly after the Second World War there was a reunion with an old acquaintance: The story goes that in 1945 Marlene Dietrich wandered with her old friend through the now overgrown garden of the Hans Albers villa on Lake Starnberg and is said to have reminisced about old times with her old acquaintance. The two had first met during the filming of the silent movie Eine Dubarry von heute (A Modern Dubarry, 1926). Hans Albers had taken a very different path from Marlene Dietrich: instead of opting to emigrate to the United States, Albers immortalized himself with German productions such as Der Mann, der Sherlock Holmes war (The Man Who Was Sherlock Holmes, 1937), Carl Peters (1941) and Münchhausen (Munchausen, 1943).

Would Hans Albers meet the same fate?

Postwar work

The late forties and early fifties were a period of uncertainty for actor Hans Albers: the system in which he was a sought-after actor no longer existed. Many actors who had enjoyed great success during the Nazi years fell out of favor after World War II and never again appeared on a theater stage or in front of a film camera. Would Hans Albers meet the same fate?

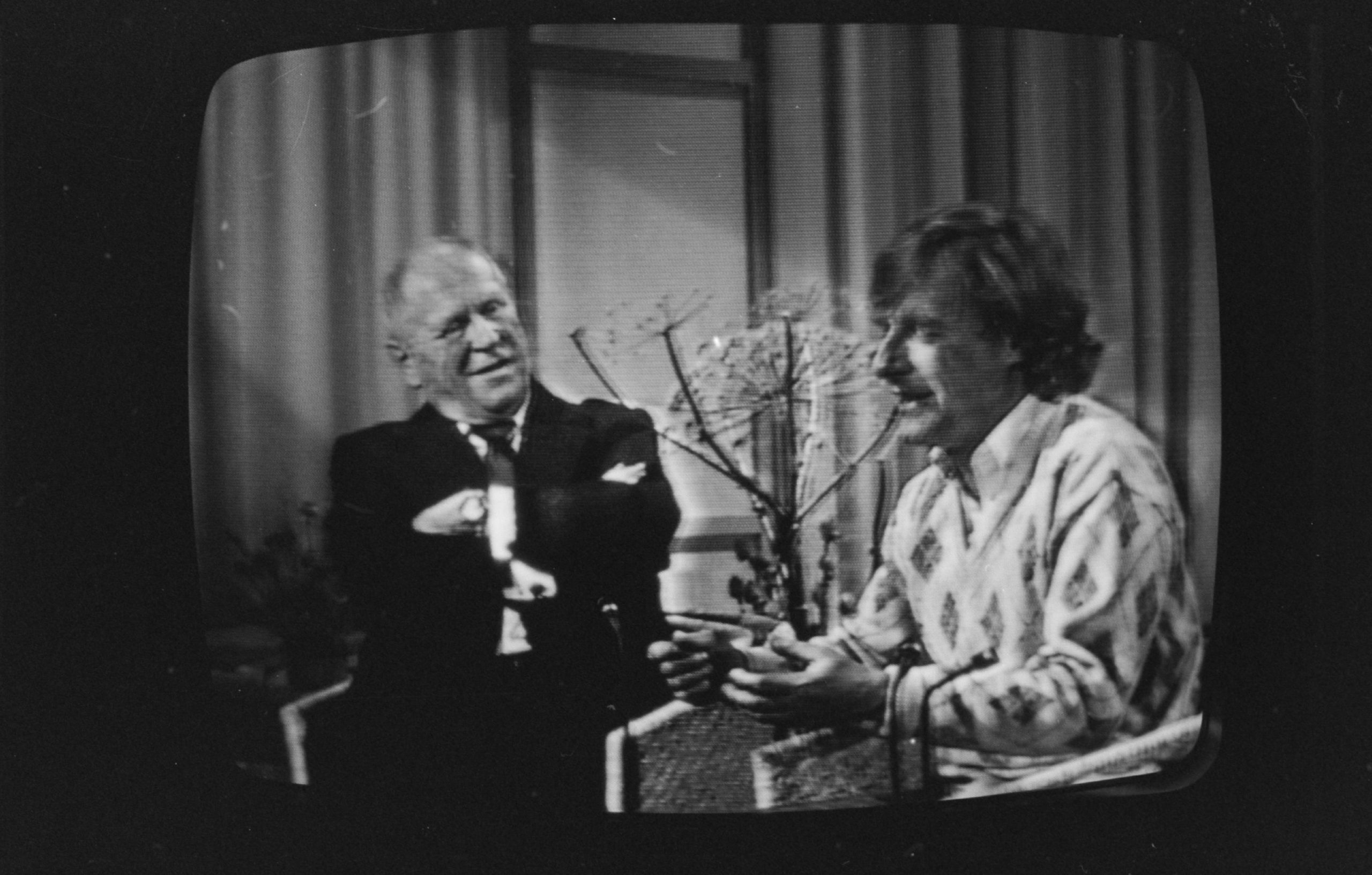

After a dip that lasted several years after World War II, Albers’ acting career was revived: the feature film Auf der Reeperbahn nachts um halb eins [“On the Reeperbahn at Half Past Midnight“, 1954], in which Albers starred alongside Heinz Rühmann, is today one of the best-known productions starring Albers and is considered a German entertainment film par excellence.

Other significant works in Albers’ later career included Der letzte Mann [The Last Man, 1955] alongside Romy Schneider and Das Herz von St. Pauli [The Heart of St. Pauli, 1957], which also starred Gert Fröbe.

Legacy – Hamburger Jung

Hans Albers takes his place among the most important German screen and theater actors of the 20th century: despite the adverse circumstances of his time, there was never any question of the actor making films in another country. With his art of acting he survived the transition from silent films to talkies and the decline of the Nazi cultural system, in which Albers played a significant role despite his critical attitude. It can be assumed that as a well-known actor he meant much more to the system than the system meant to him personally. He successfully moved in the “blind spots of a totalitarian system” (Blumenberg) and guaranteed that something remained of the legacy of those film and theater professionals who had become famous in the golden Weimar era. Although Albers spent a large part of his life on Lake Starnberg, he remained lifelong attached to his native city of Hamburg, where he was also buried after his death in 1960.

Main source: Blumenberg, Hans-Christoph. In meinem Herzen, Schatz …: Die Lebensreise des Schauspielers und Sängers Hans Albers, 2016 FISCHER

Cover picture: Hamburg, Speicherstadt, Zollfreilager (Hans Albers’ birthplace)

Picture credit: ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Bildarchiv / Photographer: Enz, Dieter / Com_LC1833-006-002 / CC BY-SA 4.0

More stories from Der Bussard

- Gert Fröbe: Goldfinger from Zwickau

- Curd Jürgens: The Grand Seigneur

- Romy Schneider: La Grande Dame

- Hildegard Knef: The Berlin Snout

Deutsch

Deutsch