This article is published on 25 March 2023 to mark the 115th anniversary of David Lean’s birth.

David Lean’s parents were Quakers: in Quaker belief, acting damages the actor’s personality and is therefore to be rejected. When he was still a boy, his parents forbade him to go to the cinema. One of the most influential film directors of the 20th century grew up under these auspices – cinema and the art of film played virtually no role in Lean’s childhood.

But cinema must have exerted a magic on David Lean even as a child: At the age of thirteen, the young Lean sneaked into the cinema with a friend and watched his first film, the silent The Hound of the Baskervilles (1921).

Lean confided in his mother that he regularly went to the cinema – his mother hid it from his father, who saw going to the cinema as a contradiction to the strict Quaker faith. In the end, young Lean even managed to get his mother to go to the cinema with him: Although she was also committed to the Quaker faith, she did not take the rules of her faith community regarding cinema and film art too seriously.

The young David Lean is said to have spent almost all his free time in the darkroom.

His first camera

At the age of ten, Lean was given a Kodak Brownie, his first camera, by an uncle. At the time, it was extremely unusual to give such a gift to a ten-year-old: In retrospect, however, this gift was more important than David Lean’s entire formal education.

When he was between fourteen and nineteen years old, he spent all his money on his hobby of photography and filming: He bought rolls of film and enlargement paper, almost all his free time is said to have been spent in the darkroom.

Without question, it was during this time in his youth when David Lean discovered his talent for photography and filming.

David Lean took his first steps in the film business when he began working at Gaumont Studios as a film clapperboard assistant in 1927: Lean came to the British film industry at a time when it was just recovering from a low point. In any case, British-made films were not particularly in demand at the time – people wanted to see the American flicks. In addition, many British banks and investors refused to invest in films – producing films was, after all, Hollywood’s job.

Working as an editor

In 1927, the Cinematograph Films Act eventually succeeded in giving the British film industry a boost: Funds were made available and a great deal of talent was recruited to help British film boom. Cinemas were obliged to show a minimum quota of British films. David Lean was one of these talents recruited: the British film industry, which had been on the verge of irrelevance, was now getting a boost.

Lean did not work as a director at first, but as an editor: among other things, he was responsible for cutting together the film material for newsreels. Later, David Lean said that the editing of a film was by far the most exciting and decisive phase that a film went through during its production: later on, he always had a contract with major productions guaranteeing that he would not only be allowed to direct the film, but would also be responsible for editing it. No matter how good a director’s work was, if the editing did not do justice to the film, the end result would not be good.

First directorial works

Initially, David Lean did not intend to become a director: Lean’s career as a director began when writer Noël Coward called him one day. Coward was known for numerous stage plays and wanted to make a film of his work in his early forties. Lean, whom he knew through his work as an editor, seemed a suitable partner for this.

The film This Happy Breed (1944) was the first time David Lean directed a film on his own – the script for the film was written by Noël Coward, as with all of David Lean’s early directing works. In retrospect, the writer Coward was the one who gave David Lean the opportunity to assert himself as a director.

The drama Great Expectations (1946) was based on the novel of the same name by Charles Dickens: David Lean made his first film independent from Coward and met Alec Guinness, who became one of his regular actors. In 1948, Lean made another Charles Dickens film: He directed Oliver Twist (1948), in which Alec Guinness again played a leading role. Today, both films are considered Charles Dickens adaptations par excellence, mainly because of Lean’s unique talent as a director.

What writers like Charles Dickens put on paper, Lean was able to stage on the screen.

Visual novelist

The German-American film director William Wyler is said to have once given David Lean the following advice: “If you’re going to shock an audience, get them almost to the point of boredom before doing so.” Lean is said to have followed this advice in many of his films – he knew better than any other director when it was time to advance the plot through dialogue and when the audience demanded a shock moment.

David Lean was considered a kind of “visual novelist”: what writers like Charles Dickens put on paper, Lean was able to stage on the screen.

David Lean showed his ability as a visual writer in the fifties and sixties: the war drama The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) marked the beginning of a whole series of successful films for Lean, which he directed: In his films, Lean did not simply tell a story, it almost always revolved around the inner conflict of the title character. This is also the case with Lawrence of Arabia (1962): The story of the main character T.E. Lawrence, played by Peter O’Toole, begins as a British officer who – he believes – is supposed to support the Arabs in their desire to become independent. When he becomes aware of the colonial powers’ real intentions, the film takes a turn: Lawrence sides with the Arabs and embraces their cultural identity. This multi-layered plot, based on an actual story, is significantly supported by Lean’s visual art: The film is still appreciated today, especially for its breathtaking desert images.

What Lean would have made of the film version of Out of Africa will always remain a mystery.

Out of Africa directed by David Lean?

At the height of his career, David Lean made only a few films, but very elaborate ones: Lawrence of Arabia alone took 20 months to shoot.

The enormously successful Lawrence of Arabia, which won seven Oscars, was followed by the even more successful Doctor Zhivago (1965). This epic romantic drama revolves around the story of the titular Dr Yuri Zhivago during the Russian revolutionary period. Omar Sharif and Alec Guinness starred in leading roles.

In the seventies and eighties, Lean realised further projects, but his work was no longer as popular with critics as before: the zeitgeist was moving away from directors like David Lean. In the eighties, David Lean expressed interest in making a film version of the literary classic Out of Africa. His project ultimately failed because he could not find a suitable producer – what Lean would have made of the film version of Out of Africa will always remain a mystery. His last directorial effort was the monumental film A Passage to India (1984), based on a novel by Edward Morgan Forster.

Fourfold talent

Leni Riefenstahl once said at a lecture in Cherbourg that it takes a fourfold talent to be a good colour film director: One must be able to convert everything one sees with one’s eyes into the optical and one must have a natural feeling for rhythm and movement – the first two talents.

The third talent: When music and sound come in, it’s not enough to be musical – it takes a cinematic musicality to know when which music fits. Last but not least, the director of a colour film must have the gift of being able to handle colours “cinematically”: This is not least about the fact that different colours trigger different states of mind in the audience. David Lean was one of the very few directors who had all these talents: He proved this with his breathtaking productions.

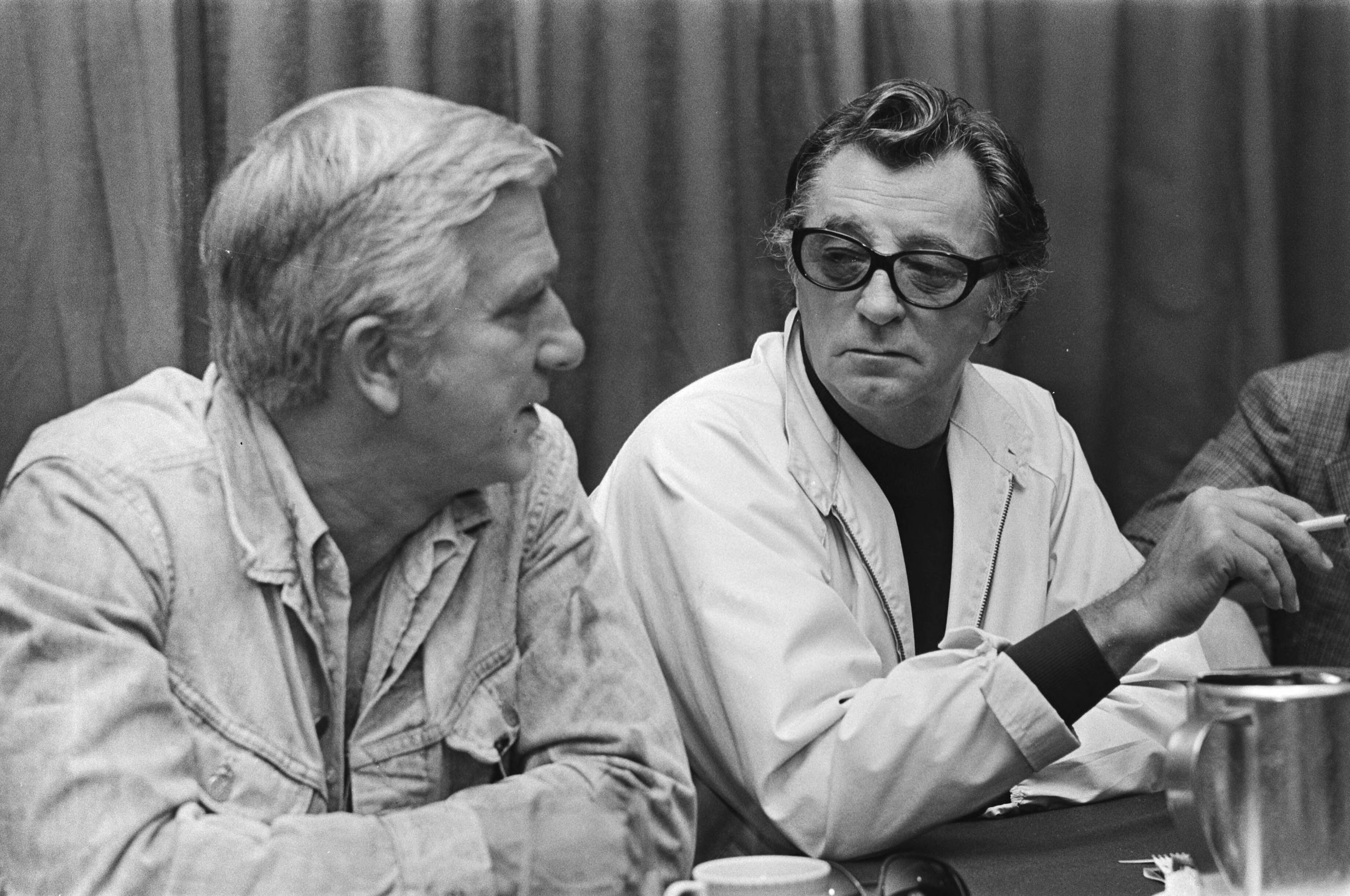

Cover picture: David Lean in 1952 at Amsterdam Schiphol airport

Picture credit: Fotograaf Harry Pot, Nationaal Archief, CC0

Main sources: Brownlow, Kevin: David Lean: A Biography, 1996 Macmillan and Riefenstahl, Leni: Memoirs, 2000 Evergreen (TASCHEN).

Deutsch

Deutsch