“Human beings don’t always seek happiness, they seek destiny.” With her work, the Danish writer Karen Blixen shaped the literature of the last century like no other writer of her generation.

She is best known for her memoir “Out of Africa”, in which she recounts her life during the time she owned and managed a coffee farm in Kenya. These memoirs, which were adapted for the cinema in 1985, are by no means just about coffee cultivation: Blixen also reflects on the indigenous African population, analyzes their culture and sheds light on the colonists’ relationship with the indigenous people from various perspectives. One could almost believe that Blixen was considered a kind of “rebel” at the time – not only did she have to put up with the accusation that she was “pro-German” during the First World War, but she was also heavily criticized by the “neighbors” of her coffee farm – including various colonialists – for her plans to provide the indigenous population with a school education…

The typical English colonialist saw himself as a missionary who populated the Kenyan land with a superior attitude.

The soul of Africa

One might think that the “soul of Africa” was crying out for a chronicler who saw herself in a position to capture a unique snapshot in the history of the African continent. The Africa that Blixen knew was an Africa that was facing a turning point.

Never again would it be possible to see how African natives and a “modern” society – represented by the English colonialists in Kenya – met and lived together.

Karen Blixen had a completely different understanding of this “living together” than most of her English neighbors: the typical English colonialist saw himself as a missionary who populated the Kenyan land with a superior attitude. Blixen saw things differently: if people like Karen Blixen had had their way, the original, untouched Kenya with its indigenous culture would not have become a “modern” Kenya, whose soul differs only marginally from that of other advanced civilizations.

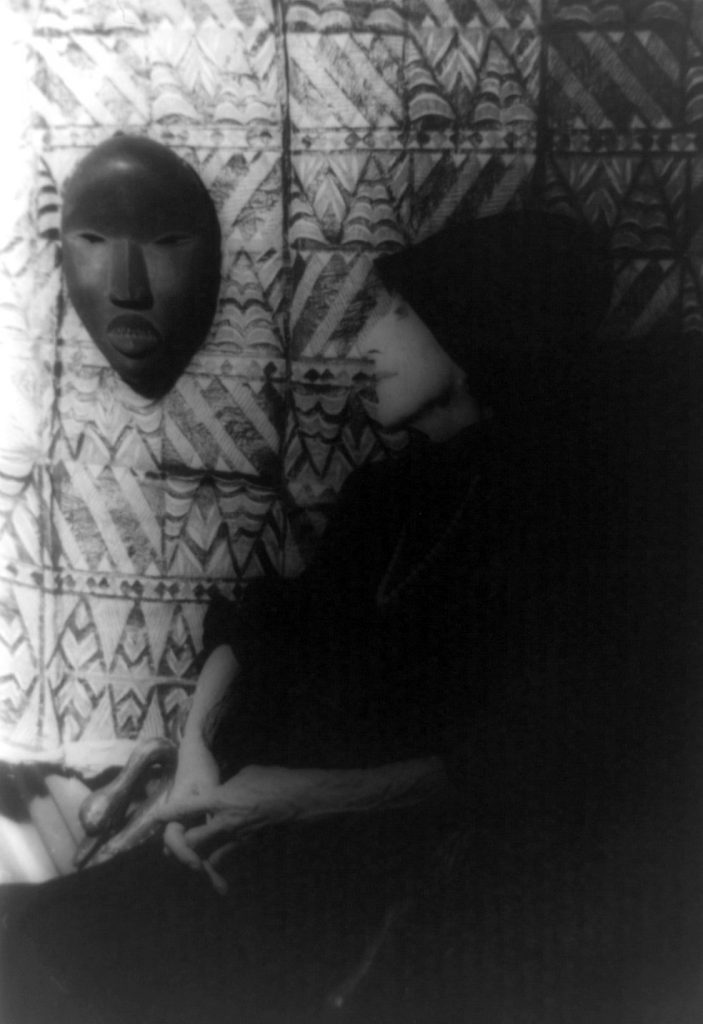

Image source: © Van Vechten Collection at Library of Congress

Merely an aristocrat?

What is left of the world that Blixen described in her memoirs “Out of Africa” – a classic of world literature? Not much or nothing at all, is the answer. Yes, the farmhouse from which Karen Blixen controlled the fortunes of her coffee farm still stands and today serves as a museum. But not much else remains from that time.

Today, Karen Blixen tends to be condemned for her “aristocratic” world view and pigeonholed with other, far more narrow-minded authors and personalities of the time.

If one reads Karen Blixen’s work – there are numerous essays and works by her about her time in Africa, even apart from “Out of Africa” – one realizes that Blixen must have been the last person there with an aristocratic attitude.

The flair of aristocratic authority

In her works, she even goes so far as to claim that the indigenous culture of the Maasai and the Kikuyu was far ahead of the European culture of the time – in numerous passages she expresses her admiration for their culture, in some places this admiration even turns into envy.

Are these the words of an “aristocrat”? No, rather they are the words of a progressive-minded woman who took advantage of her social status as an aristocrat at the time to lend her far-sightedness the air of aristocratic authority.

It would appear that the Kenyan natives of the time had an ardent advocate in Baroness von Blixen-Finnecke. Why else would Blixen have campaigned for the indigenous people to remain on the land they had inhabited for generations after leaving Kenya?

At some points, the film provides hints that can only be fully understood by reading Blixen’s works.

More than just a love story

Her time in Africa inspired Blixen to create literary works that have never been seen in this form a second time and probably never will be again. The 1985 film adaptation of her memoirs, starring Meryl Streep and Robert Redford, did much to popularize Blixen’s legacy around the world thanks to Sydney Pollack’s literary adaptation. Contrary to what is often claimed, the film is not just about the love story between the Baroness and an urbane Englishman named Denys Finch-Hatton: The film makes an attempt – as far as it is possible within the framework of Hollywood cinema – to come to terms with the complex and multi-layered legacy of the Baroness von Blixen-Finnecke and to work out what was really significant in her work.

At some points, the film provides hints that can only be fully understood by reading Blixen’s works. Be it the colonial period or historical events such as the First World War, the film deals with these events and their impact on life in the colony at the time.

The “old world”

In the end, however, it was not the world view of Karen Blixen that determined the further course of Kenya’s history. Modern civilization and the spirit of human progress, two concepts that are difficult if not impossible to reconcile with a thriving indigenous culture, pushed back that previously untouched world and in a sense “swallowed up” the “Old World”.

What remains are Blixen’s works and her legacy – one wonders what would have become of the soul of “old Kenya” if there had been no chronicler like Karen Blixen to immortalize that time in her memoirs and record it for future generations.

Who would still know today what it means to wait for the rain that never comes to nourish the thirsty coffee plants on whose growth one’s own economic success depends?

Cover picture: Karen Blixen in 1959 on a photography by Carl van Vechten, © Carl van Vechten

Image source: © Van Vechten Collection at Library of Congress

Deutsch

Deutsch