Continued from part two

In 1949 Max Lichtegg celebrated a kind of “return to Vienna” – to the city where his musical career had begun. Lichtegg gained a reputation as an accomplished operatic tenor in various roles, including Rossini’s Barber of Seville or Bizet’s Carmen. The tenor was given a holiday from the operetta genre – unfortunately it did not come to a permanent contractual relationship with the Vienna State Opera that went beyond guest performances.

With time, the engagement in Zurich also proved problematic, so it was regrettable that Lichtegg could not enter into a firm commitment with the Vienna State Opera.

In the fifties, there were various requests from all over the world for engagements – the agent William Stein repeatedly gave Lichtegg hope for an American breakthrough. After numerous disillusionments, however, Lichtegg no longer expected such a breakthrough to happen.

Great notoriety

Apart from that, foreign successes were anything but well received at his home theatre in Zurich: Not least because of this, a separation from the Zurich City Theatre was on the horizon. In addition, Lichtegg’s fees were almost ridiculously low compared to those of other opera and operetta stars. Even Maria Callas later said in an interview that she had a certain fortune, but would by no means call herself rich – how must Lichtegg have felt? The fact that Lichtegg stayed in Zurich despite these financial circumstances is further proof that for Max Lichtegg, it was all about art. For the time being, Zurich was the best way to fulfil the artistic demands he placed on himself and his art.

From the 1951/1952 season onwards, Lichtegg only signed six-month guest contracts with Zurich: the tenor saw this as preparation for other, international engagements.

In the meantime, his fame in Switzerland had reached gigantic proportions – by Swiss standards: if a fashion show was being held by a renowned Swiss fashion manufacturer, it was customary to invite Max Lichtegg to provide the musical background for the evening.

At a time when fashion shows were the only source of information for people interested in fashion, such a show had an important status.

“Artistically completely switched off”

By the end of January 1953, it was enough: Max Lichtegg noted in his diary, “Artistically completely switched off – no more good roles.” The end of his engagement in Zurich was looming. Would the end of his Zurich commitments mean a springboard into the big, wide world?

The conductor Otto Ackermann had meanwhile become a constant companion of Max Lichtegg: Already during Lichtegg’s time in Bern, Ackermann stood by him in an advisory capacity. The two worked together during an engagement for the Opéra de Monte Carlo at the end of February 1953 in Carl Maria von Weber’s Freischütz. It was not to be the last time Max Lichtegg would perform in Monte Carlo. Two years later, Lichtegg appeared again in Monte Carlo, this time in Boris Godunov (Mussorgsky). The opera house of the small, but prestigious principality of Monaco seemed an ideal place for the tenor Max Lichtegg to demonstrate his vocal abilities.

The concert tours were a welcome opportunity for Lichtegg to showcase all aspects of his repertoire, which included operas, operettas and Lieder.

New opportunities

In mid-1954 Max Lichtegg finally terminated his contract with the Zurich City Theatre: for the singer it was the end of an era, which at the same time offered numerous opportunities.

One such new opportunity opened up immediately in Max Lichtegg’s career:

The agent Eynar Grabowsky initiated a new phase in Max Lichtegg’s career in 1956. Grabowsky organised a tour for Lichtegg with 34 concerts throughout Switzerland – the tour was a great success and raised the tenor’s profile. Grabowsky was to actively support the tenor as manager in the years to come.

Further concert tours in Switzerland and abroad were scheduled for the next few years: The concert tours were a welcome opportunity for Lichtegg to showcase all aspects of his repertoire, which included operas, operettas and Lieder.

Max Lichtegg and the operetta

On the occasion of a performance of the Lehár operetta Land des Lächelns in 1961 at the Kongresshausbühne Zurich, Max Lichtegg made the following statement:

“Why do I like to sing Lehár? The art of composing for the human voice is increasingly on the wane. (…) Franz Lehár knew the conduct of the human voice and thus also the effect of vocal expression. (…) He was the ‘singers’ composer‘. (…) Through Lehár, the singer finds in operetta the identity of the singer: the opportunity ‘sing beautifully‘, or as the old term ‘bel canto‘, unfortunately often abused and forgotten in its true meaning, puts it. And that is why, as long as there will be vocal art, there will certainly be Franz Lehár.”

Fassbind, Alfred A.: Max Lichtegg – Nur der Musik verpflichtet [Only Committed to Music], 2016 Römerhof publishing house Zurich, p. 391f. (Translated from German)

This statement shows Max Lichtegg’s relationship to operetta: It was a response to those critics who wanted to degrade him to an “operetta tenor“ – yet operetta is no less a component of bel canto in its modern form.

The modern bel canto

However, bel canto in its modern form was far from being recognised at the time: Max Lichtegg addresses the aspect of “singing beautifully” – many of his listeners appreciated precisely that aspect of his singing style. Many singers and experts committed to bel canto saw things quite differently from Max Lichtegg at the time: bel canto did not mean “singing beautifully” alone, Maria Callas once told her students at the Juilliard School in the seventies. Bel canto is much more about the vocal requirements of the composers of the bel canto style, the opera diva said. It is not necessarily about singing beautifully – if the scene requires it, one must even be prepared to sing harshly and in a shrill tone. After all, opera is a play. This was the opinion of Callas and possibly other influential experts of the time.

Ahead of his time

The tenor Max Lichtegg was thus the representative of a type of singer who was little represented on the international stage at the time. The art of “singing beautifully”, as Max Lichtegg perfectly mastered it, was in demand by the public, but the time was not yet ripe for this kind of singer, so to speak. At that time, other standards applied and many experts would not have counted operetta as bel canto even in a nightmare: This is precisely what became Max Lichtegg’s undoing throughout his career. The time was not yet ripe for the universal approach to the art of singing that Lichtegg aspired to.

Max Lichtegg was a kind of universal tenor: moreover, he was not afraid to revive works by composers who had already fallen into oblivion. Thus Max Lichtegg was not only a preserver of the art of bel canto, but also a pioneer of “modern bel canto”.

Der Bussard expresses its gratitude to Mr Alfred Fassbind from Rüti near Zurich, author of the Max Lichtegg biography, for his cooperation.

The standard biographical work on Max Lichtegg written by Mr Fassbind, published in 2016 by Römerhof Verlag (Zurich), was kindly provided to Der Bussard. The biography served as the main source for the article.

Publication information: Fassbind, Alfred A.: Max Lichtegg – Nur der Musik verpflichtet [Only Committed to Music], 2016 Römerhof publishing house Zurich

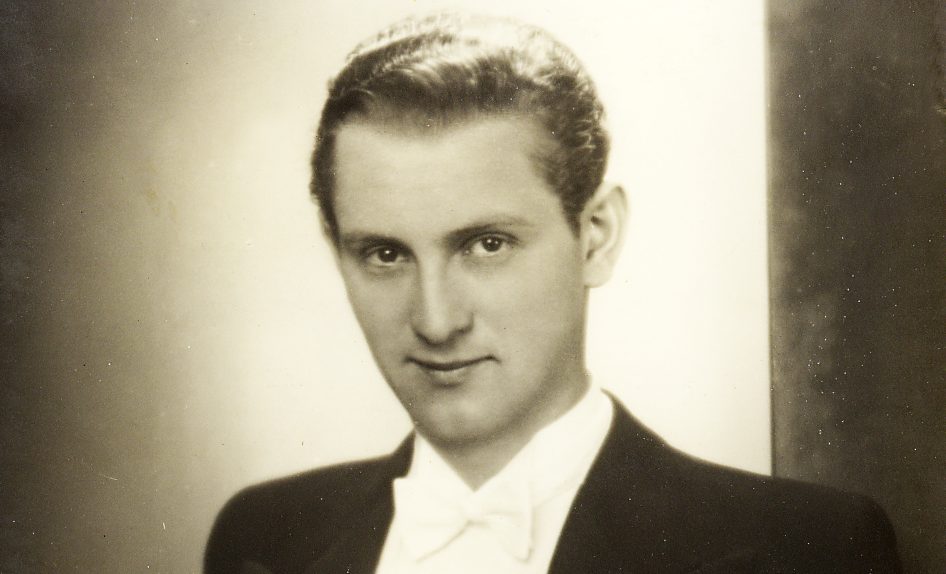

Cover picture: Max Lichtegg with Dagmar Koller on television in 1970. By courtesy of Alfred Fassbind.

Deutsch

Deutsch Français

Français