Wine production in Italy used to be in the hands of the landowners: the farmers had to deliver the grapes for the wine – the farmers were only allowed to keep one thing: the grape residues that remained after pressing. Many hundreds of years ago, farmers first distilled a product similar to today’s grappa from this pomace, which consists of grape skins and grape seeds, among other things. At first, grappa was nothing more than a simple farmer’s brandy.

It was much later that grappa began its successful journey around the world: In the 20th century, the possibilities of distillation improved and the quality of the farmer’s brandy improved significantly. The fact that grape skins could also be distilled into an aromatic eau-de-vie soon fascinated schnapps connoisseurs from all over the world.

The distillation

It is not known exactly when grappa was first distilled: The only certainty is that the Arabs, starting from Sicily in the 9th century, spread the concept of distillation throughout Europe. Since distillation is the precondition for the production of grappa, it seems obvious that the production of the first grappa took place around the same time.

After the beginning of the Crusades in the 11th century, distillation played a major role in Europe: the first organised grappa trade took place from the 15th century onwards, even outside Italy.

Although the production of grappa was strictly regulated at first, farmers were allowed to produce a small amount for their own use in order to make use of the pomace. This gave grappa the nickname “farmer’s brandy”.

A grappa would be nothing without its fruit aromas.

Grappa: Produced wherever there is viticulture

In the Middle Ages, various doctors studied the effects of distillates on the human body. Quite often, research in this field was stopped and the production of distillates was consequently subject to high taxes.

There is one rule in the production of grappa: where there is a lot of viticulture, grappa is also produced.

A grappa would be nothing without its fruit aromas: the grapes whose pomace is used to make grappa must be healthy and fully ripe. It is also crucial that the pomace used is fresh: immediately after the pressing process is completed, the distiller collects the pomace from the vintner. The longer the pomace rests untreated at the vintner’s, the poorer the quality of the pomace becomes due to oxidation and various microbiological processes.

Production of grappa

100 kilograms of fresh, moist pomace produce about 10 litres of grappa: In the distillation of grappa, a distinction is made between the discontinuous method and the continuous method. The discontinuous method is the most common and requires cleaning of the equipment after each distillation process. With the continuous method, this cleaning is not required: In this way, large quantities of pomace can be processed into grappa within a very short time.

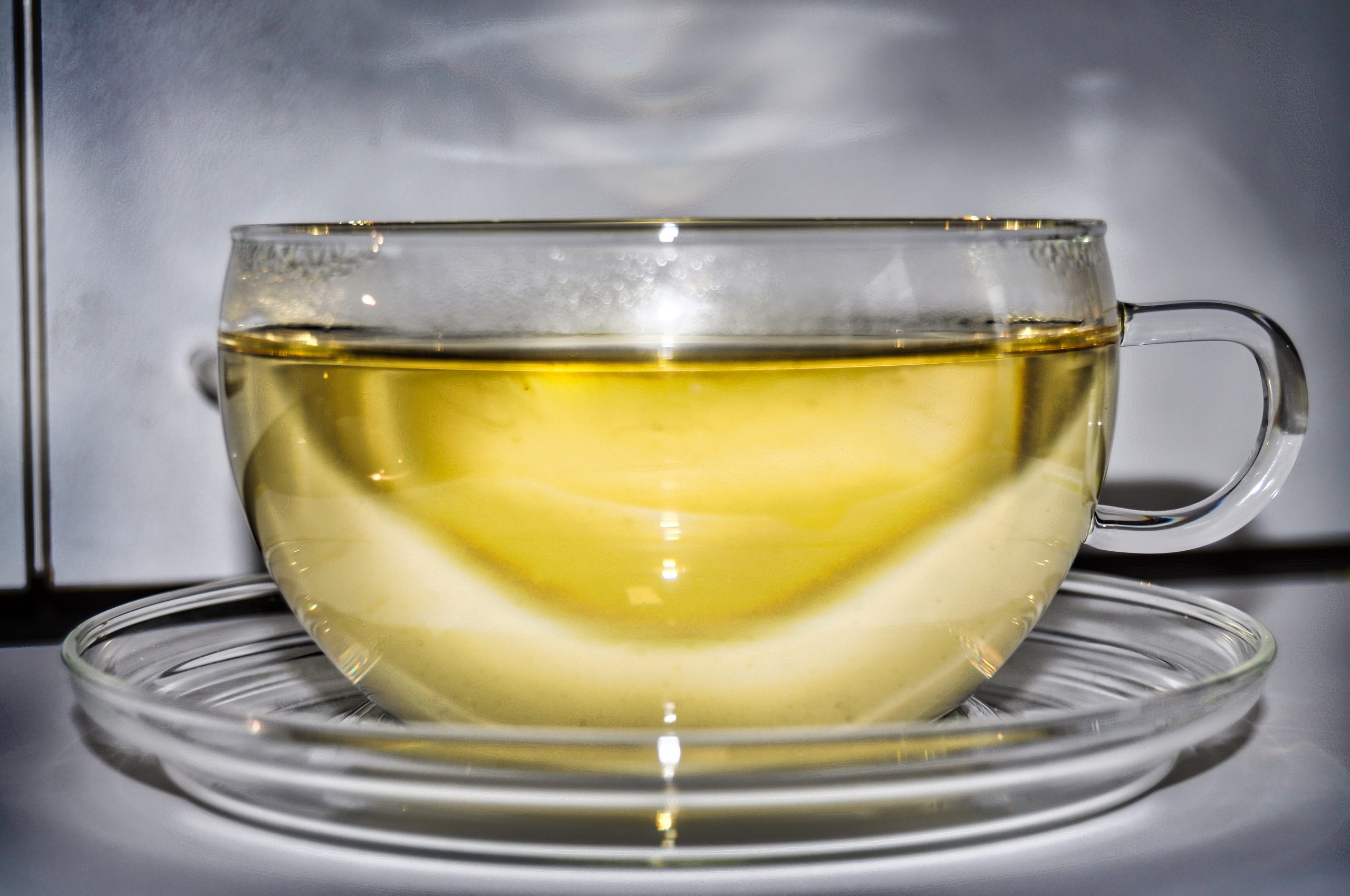

In the past, the stills in which the grappa is distilled were fired directly: because of the danger of the product burning at the bottom of the still, this method is hardly used any more. Today, distilleries instead rely on water bath heating and steam distillation. After distillation, a colourless distillate is obtained: there is still no sign of the yellowish colour that characterises a grappa that is ready to drink.

After distillation, grappa is stored in wooden barrels: This creates special taste nuances. The wood breathes and the distillate comes into contact with oxygen: this rounds off the flavour of the distillate and gives it a sweet taste.

The choice of wood has a great influence on the taste of the grappa.

Maturation

Grappa is often aged in oak barrels: However, there is also grappa that is stored in oak, chestnut, apple or cherry wood barrels. The choice of wood has a great influence on the taste of the grappa: oak wood is considered mildly aromatic and contains tannins, which is why oak barrels (also called barrique) are particularly often used for ageing grappa. Other woods give the grappa a different flavour impact, which is less in demand.

Basically, the longer the grappa matures, the more aromatic the grappa becomes and the more the product tends to lose its pungency. As with many other spirits, connoisseurs are convinced that a longer storage time makes the product more valuable.

If a grappa is bottled fresh after the maturing period, the alcohol content is between 70 and 85 percent by volume. Immediately after bottling, the product is reduced to a drinking strength of 38 to 50 percent by volume by adding demineralised water. It is only then that the grappa becomes drinkable.

Evolution towards a noble distillate

Only distillates distilled from Italian pomaces are allowed to bear the name grappa: the first Italian distillery for spirits of all kinds was founded in 1779 – at a time when the name grappa did not even exist. Although there were pomace brandies, they bore the simple name “Acquavite” (Italian for schnapps).

Until the late 20th century, grappa was anything but a noble distillate: until recently, grappa still had a reputation as a farmer’s brandy, as anything left over from wine production was distilled. Only slowly it became clear that a unique product could be produced by cherry-picking the best from the pomace: some distilleries started distilling the best grape residues in the eighties and thus made grappa the noble distillate it is today.

Cover picture: © Simon von Ludwig

Deutsch

Deutsch